4-teachers

- Home /

- 4-teachers

![]() The aim of Hopscotch 4-Teachers is to provide teachers with a tool to assist them in designing a thorough inquiry process to promote the “systematic collection, analysis, examination, and interpretation of data to inform practice and policy in educational settings” (Mandinach, 2012, p. 71). After submitting your answers, the system will send you an email with the generated design. You will also receive a link to edit the design as many times as needed.

The aim of Hopscotch 4-Teachers is to provide teachers with a tool to assist them in designing a thorough inquiry process to promote the “systematic collection, analysis, examination, and interpretation of data to inform practice and policy in educational settings” (Mandinach, 2012, p. 71). After submitting your answers, the system will send you an email with the generated design. You will also receive a link to edit the design as many times as needed.

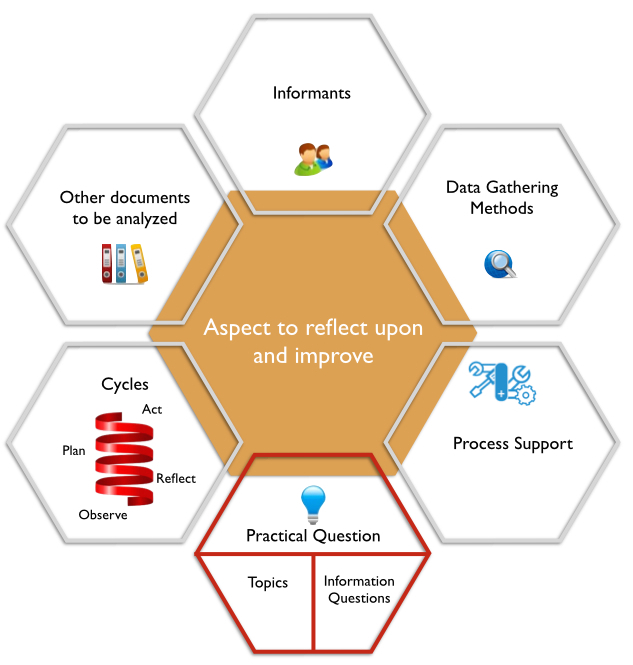

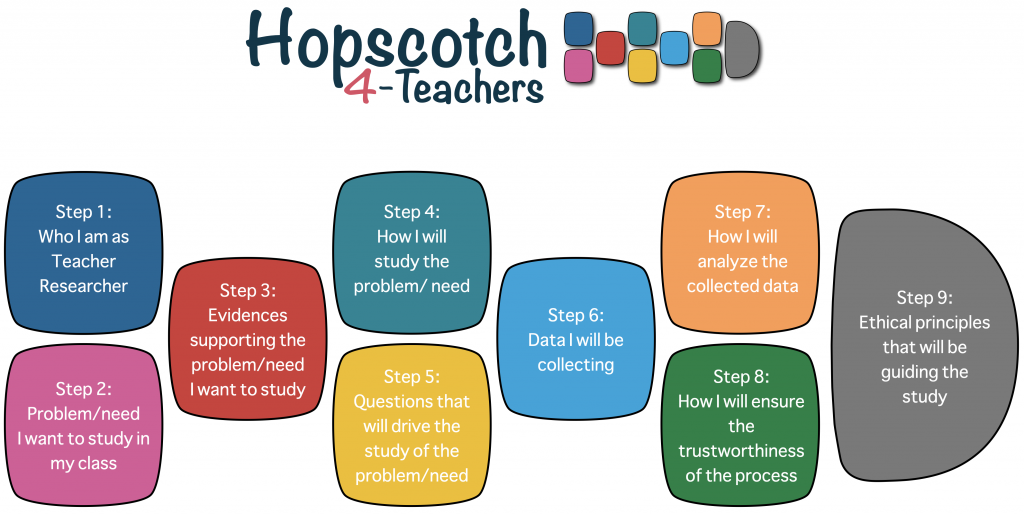

You can find below the nine steps we propose you to follow in order to generate a thorough research design to investigate a problem, need, or innovation in your classroom:

The first step in the process of generating a design for your classroom study has to do with reflecting about who you are as a teacher researcher. We propose you to think about the following areas that will have a key impact in your study:

The first step in the process of generating a design for your classroom study has to do with reflecting about who you are as a teacher researcher. We propose you to think about the following areas that will have a key impact in your study:

Years in the profession and teaching area/subject

Your experience as a teacher matters when getting involved in a study. The more experience you have, the easier it will be for you to analyze the problem, need or innovation that you are interested in studying.

Collaboration with "critical friends"

The European Centre for Modern Languages of the Council of Europe, recommends teachers conducting classroom research to count with the help of group of colleagues or critical friends.

You may find it helpful to identify a critical friend who can support you with your action research. The term ‘critical friend’ or ‘critical colleague’ as first used by Stenhouse in 1975 who proposed that a critical friend can give advice and can work with teacher-researchers during action research. This is also referred to as a ‘learning partner’ (McNiff, 2002).

A critical friend could be a colleague who is interested in what you are doing with your research. Their role is to listen as you talk through and clarify your ideas and who can provide honest and impartial feedback. This will help you to adopt a more independent stance towards your own action research project and to ensure that your research plan is coherent. As McNiff (2002) states, critical evaluation is a key component in maintaining the quality of your research.

Feldman, Altrichter, Posch and Somekh (2018) recommend the following steps when working with a critical friend:

1. Hold a preliminary conversation so that you can talk about the starting points of your research;

2. Move onto talking about ideas for the initial stages of the research.

They also argue that conditions for action research are more favourable when a small group of action researchers work together and can share experiences.

- Baskerville, D. & Goldblatt, H. (2009) Learning to be a critical friend: from professional indifference through challenge to unguarded conversations. Cambridge Journal of Education 39 (2): 205-221. (check article)

- Critical friends – Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) Guide 2014 (check guide)

- Feldman, A., Altrichter, H., Posch, P. & Somekh, B. (2018) Teachers Investigate Their Work: An Introduction to Action Research across the Professions. 3rd edition. London: Routledge. (check book)

- Kember, D., Ha, T-S., Lam, B-H, Lee, A. NG, S. Yan, L. & Yum, J.C.K. (1997) The diverse role of the critical friend in supporting educational action research projects. Educational Action Research 5 (3), 463-481. (check article)

- McNiff, J. (2002) Action Research for Professional Development. 3rd edition. (check guide)

Teaching Style

"Effective learning in the classroom depends on the teacher's ability to maintain the interest that brought students to the course in the first place" (Ericksen, 1978).

Therefore, your teaching style is going to be a key factor impacting almost every activity that happens within the walls of your classroom. No matter if you are interested in analyzing how an innovation that you have recently implemented is working, the ways to better help your student learn a particular content, or a certain models to better respond to the needs of your students, your teaching style is going to affect the study.

Imagine that you are interested in studying the impact that a project-based learning lesson is having in promoting deep learning among your students. The successful implementation of this particular innovation would require a teacher with a student-centered approach to learning that is able to promote critical thinking and lively discussion by asking students to respond to challenging questions. A directive style (teacher-centered approach) based on the promotion of learning through listening and following directions, might not be appropriate for the aforementioned innovation.

A potential way of reflecting on your teaching perspective/ style would be using the Teaching Perspectives Inventory (TPI) (Pratt et al., 2000). It is a free survey that can be of help to reflect on your teaching beliefs, intentions, and actions. The TPI survey has been used internationally for teacher's individual reflection and for groups of teachers to reflect on their collective teaching perspectives. It proposes five perspectives on teaching that you will find in the following tabs.

The Teaching Perspectives Inventory (TPI) (Pratt et al., 2000) is a free survey that can be of help to reflect on your teaching beliefs, intentions, and actions. It proposes the following five perspectives on teaching that you will find in the following tabs.

From a Transmission Perspective, effective teaching assumes instructors will have mastery over their Those who see Transmission as their dominant perspective are committed, sometimes passionately, to their content or subject matter. They believe their content is a relatively well-defined and stable body of knowledge and skills. It is the learners’ responsibility to master that content. The instructional process is shaped and guided by the content. It is the teacher’s primary responsibility to present the content accurately and efficiently to learners.

From an Apprenticeship Perspective, effective teaching assumes that instructors will be experienced practitioners of what they are teaching. Those who hold Apprenticeship as their dominant perspective are committed to having learners observe them in action, doing what it is that learners must They believe, rather passionately, that teaching and learning are most effective when people are working on authentic tasks in real settings of application or practice. Therefore, the instructional process is often a combination of demonstration, observation and guided practice, with learners gradually doing more and more of the work.

From a Developmental Perspective, effective teaching begins with the learners’ prior knowledge of the content and skills to be Instructors holding a Developmental dominant perspective are committed to restructuring how people think about the content. They believe in the emergence of increasingly complex and sophisticated cognitive structures related to thinking about content. The key to changing those structures lies in a combination of effective questioning and ‘bridging’ knowledge that challenges learners to move from relatively simple to more complex forms of thinking.

From a Nurturing Perspective, effective teaching must respect the learner’s self-concept and self-efficacy. Instructors holding Nurturing as their dominant perspective care deeply about their learners, working to support effort as much as achievement. They are committed to the whole person and certainly not just the intellect of the learner. They believe passionately, that anything that threatens the self-concept interferes with learning. There-fore, their teaching always strives for a balance between challenging people to do their best, while supporting and nurturing their efforts to be successful.

From a Social Reform Perspective, effective teaching is the pursuit of social change more than individual Instructors holding Social Reform as their dominant perspective are deeply committed to social issues and structural changes in society. Both content and learners are secondary to large-scale change in society. Instructors are clear and articulate about what changes must take place, and their teaching reflects this clarity of purpose. They have no difficulty justifying the use of their teaching as an instrument of social change. Even when teaching, their professional identity is as an advocate for the changes they wish to bring about in society.

You can also find relevant information and resources regarding your teaching style in this site that sponsored by Harvard's Bok Center for Teaching & Learning.

Worldview as a teacher researcher

Your teaching perspective will be deeply connected to your worldview or paradigmatic positioning as a teacher researcher. Teacher researchers bring to their studies their particular way of understanding how things work in our world, and the way knowledge is constructed. The worldview of the researcher as well as his/her adscription to a particular Interpretive Community (i.e. disability theory; critical race theory; queer theory, etc) is going to have a deep impact in the decisions and inquiry procedures he/she will put in practice. Guba (1990) describes a paradigm or worldview as "a basic set of beliefs that guide action.” That basic set of beliefs of the researcher is based on his ontological (What is the nature of reality?) and epistemological assumptions (What is the nature of knowledge and the relationship between the knower and the would-be known?). Therefore, how one views the constructs of social reality and knowledge affects how they will go about uncovering knowledge of relationships among phenomena and social behavior. Your ontological assumptions inform your epistemological assumptions which inform your methodology and these all give rise to your methods employed to collect data. From an ontological point of view, post-positivism understands that there is one reality which is knowable within a specific level of probability, while constructivism understands that the nature of reality is multiple and socially constructed. Pragmatism asserts that there is a single reality and that all individuals have their own unique interpretation of reality. Finally, those following a transformative worldview reject cultural relativism and recognize that various versions of reality are based on social positioning. From an epistemological point of view, post-positivists believe that objectivity is key and than the researcher manipulates and observes in a dispassionate objective manner. Constructivists on the contrary, believe that there should be an interactive link between researcher and participants, and that since knowledge is socially and historically situated, it needs to address issues of power and trust. Pragmatism on its side, understands that relationships in research are determined by what the researcher deems as appropriate to a particular given study. Finally, a transformative worldview acknowledges that since there is an interactive link between researcher and participants, and knowledge is socially and historically situated, there is a clear need to address issues of power and trust. These ontological and epistemological assumptions have a direct impact in the methodology used in a given study. Post-positivism calls for interventionist quantitative studies, while constructivism prefers qualitative hermeneutical studies, and pragmatists matches methods to specific questions and purposes of research by using mixed methods. In the case of researchers following a transformative worldview, qualitative methods deeply grounded in critical theories, are the most common ones. Please watch the following clip to clarify the previous concepts:

The second step in the process of of generating a design for your classroom study has to do with reflecting about what you would like to study, and the goals that will be driving your study. We propose you to think about the following areas that will have a key impact in your study:

Defining what you would like to study

Beginning your classroom research study requires reflecting upon the problem, need innovation, activity, etc that you want to study. As it is recommended by Frances Rust and Christopher Clark's guide to action research, to do so it will be important to adopt a professional stance that is centered around inquiry—asking questions about things that others might take for granted. Examples of questions that might be of help in identifying the "topic" under study are:

- What am I curious or puzzled about in my teaching?

- What is working in your classroom, in your teaching?

- Who is learning?

- Who is being left out?

- How does your curriculum provide opportunity to learn?

- When do you feel like you’re “losing it”?

Questions such as the previous can be uncomfortable to ask. They may produce even more discomforting answers. But, unless and until teachers grapple with the hard questions, we will remain powerless to do very much to improve life in classrooms. Samaras (2011) provides the following example on how we could answer the question "What do you wonder about in your teaching practice?":

- I wonder about what role I can play as a Hispanic teacher in helping Hispanic students survive and understand biology.

Other topics that you could study in your classroom are:

- Changes in classroom practice.

- Effects of program restructuring.

- New understanding of students.

- Teacher skills and competencies.

- New professional relationships.

- New content or curricula

Goals driving your study

Maxwell (2008) states that goals include motives, desires, and purposes—anything that leads you to do the study or that you hope to accomplish by doing it.)

Some questions that could help you better define the goals of your classroom study are:

- Why is your study worth doing?

- What issues do you want it to clarify, and what practices and policies do you want it to influence?

- Why do you want to conduct this study, and why should we care about the results?

According to (Maxwell, 2008), goals serve two main functions for your research:

- They help guide your other design decisions to ensure that your study is worth doing.

- They are essential to justifying your study, a key task of a funding or dissertation proposal.

There are three kinds of goals for doing a study (Maxwell, 2008):

- Personal goals: those that motivate you to do this study; they can include a desire to change some existing situation, a curiosity about a specific phenomenon or event, or simply the need to advance your career.

- Practical goals: are focused on accomplishing something—meeting some need, changing some situation, or achieving some goal.

- Intellectual goals: re focused on understanding something, gaining some insight into what is going on and why this is happening.

The third step in the process of of generating a design for your classroom study has to do with reflecting about the interest I have in what I want to study, and its relationships with what others have already studied. We propose you to think about the following areas that will have a key impact in your study:

Interest in studying this particular problem, issue, innovation, need, activity

In order to reinforce what you have already defined in step 2, it would be relevant to reflect on the interest you have in studying your topic.

Samaras (2001) provides the following examples to illustrate the answers we are looking for in this regard:

- Why are you interested in studying this particular problem, issue, innovation, need? This question is important to me because of my background as a Hispanic and the fact that I was an ESOL [English as a Second Language] student for a brief period of time.

- Who would benefit from addressing/studying the previous particular problem, issue, innovation, need? Many would benefit from addressing this question: ESOL [English for Speakers of Other Languages]teachers, students, parents, and other teachers. I want to work to improve ESOL students’ weak performance in school.

Evidence-based practices supporting what you would like to study

A second relevant aspect would be for you to identify if what you will be studying is supported or based on an evidence-based practice. Evidenced-based practices are those “effective educational strategies supported by evidence and research” (ESEA, 2002). When teachers use evidence-based practices with fidelity, they can be confident their teaching is likely to better support student learning and achievement.

The IRIS Center offers a free Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Module series that takes education professionals through the step-by-process of identifying, selecting, implementing, and evaluating evidence-based practices, including procedures for scenarios when the research is insufficient.”

It might be a helpful resource to identify if what you are interested in studying is or it is related with a particular Evidence-based Practice.

A second resource that you could use to identify Evidence-based practices, is John Hopkins' Best Evidence Encyclopedia (BEE). This resource presents reliable, unbiased reviews of research-proven educational programs to help policy makers use evidence to make informed choices, principals choose proven programs to meet state standards, Teachers use the most powerful tools available, and researchers find rigorous evaluations of educational programs.

Previous studies addressing the same or a similar problem, issue, innovation, need, activity

The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) reviews the existing research on different programs, products, practices, and policies in education. Their goal is to provide educators with the information they need to make evidence-based decisions. WWC focuses on the results from high-quality research to answer the question “What works in education?”

We recommend using "Find what works based on evidence" in order to identify previous studies regarding what you are interested in studying. The information, articles, experiences and reports retrieved from WWC will be instrumental in helping better understand your research topic.

The following video might be of help tp understand how WWC works:

The fourth step in the process of of generating a design for your classroom study has to do with learning a little about the classroom action research approach to research.

Frances Rust and Christopher Clark's guide to action research defines it in the following way:

- Classroom action research is a rather simple set of ideas and techniques that can introduce you to the power of systematic reflection on your practice. Our basic assumption is that you have within you the power to meet all the challenges of the teaching profession. Furthermore, you can meet these challenges without wearing yourself down to a nub. The secret of success in the profession of teaching is to continually grow and learn. Action research is a way for you to continue to grow and learn by making use of your own experiences. The only theories involved are the ideas that you already use to make sense of your experience. Action research literally starts where you are and will take you as far as you want to go.

The Drawn to Science website (part of Project Nexus, a National Science Foundation supported project in the Teacher Professional Continuum Program (ESI, 0455752), offers examples of good action research studies:

In addition to previous resources, we also encourage you to check Frances Rust and Christopher Clark's guide to action research.

The following video might also be of help to know more a bout classroom action research:

Frances Rust and Christopher Clark's guide to action research offers the following tips in developing the research question/s for your classroom study:

The hardest part of designing an action research study is framing a good question. Avoid questions that can be answered with “yes” or “no.” Avoid questions to which you already know the answer (action research is not very good at proving that “method A is superior to method B”). Action research helps you understand the consequences of your action.

So what makes for a good question?

We have found that good questions are free of educational jargon. They use simple everyday words that make the point clear to all. They do not prejudge the result. One of the first activities you can do is make a list of questions and topics that you have about your classroom or your teaching or both. Try starting with, “I wonder what would happen if . . . ” (This could be part of your 10 minutes a day.) You can always reframe a statement as a question. Choose one question or topic on which you can spend some time. Ask yourself why this question is interesting to you, how you might go about answering it, and what might be the benefit of answering it. If, after this conversation with yourself, you are still interested in the question, do a reality check by trying it out on a colleague.

Developing your question

- Write a first draft

- Share it with a colleague (critical friends)

- Grow it a little—make it researchable

Questions emerge in different forms. Most often, the first draft of the question is steeped in the reality of your classroom. We call these first draft questions. As an example, take the following question: “Why are some kids in my class so mean and nasty to each other?” Following the advice we’ve just given you, if this were your question, you would go off to a colleague or friend and try it out. In the process, you would begin to think about how on earth you’re going to answer that question in a way that would help you to improve the situation. In other words, we don’t want you to say to yourself, “Oh. It’s their parents!” The answer for you has to include something that you can do, some action that you can take in your classroom.

So, the question is likely to change to become more researchable. “How can I help the kids in my class develop a respectful classroom community?” would lead you toward action.

Resources to help you develop Research Questions in Qualitative Studies

- Jane Agee (2009) Developing qualitative research questions: a reflective process, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22:4, 431-447, DOI: 10.1080/09518390902736512

- Check out www.teachersnetwork.org/tnli/research for other examples of researchable questions that have led to successful studies.

The sixth step of the process has to do with defining the data collection methods that you will be using in your classroom study. The following two questions might be of help in doping so:

- What evidence do you need to convince yourself that you’ve answered your question?

- What tools do you use everyday that would provide that evidence?

Frances Rust and Christopher Clark's guide to action research offers the following tips: For example, let’s go to our question about developing a respectful classroom community. Implicit in the first draft of that question was plenty of evidence that the kids in that classroom were having a terrible time with one another. Probably, the teacher had noted behaviors that for her were markers of a disrespectful tone. She probably knew who the most conspicuously difficult kids were. She probably even had notes to the principal and to parents. All of that data was probably gathered through what researchers call anecdotal records. And you undoubtedly collect similar information in the same way. So you already have a tool at your disposal. Others that teachers use everyday include: CLASSROOM MAPS: Don’t forget to draw a map! Once you’ve done that, you can make multiple copies and use them to help you gather data to answer a variety of questions like those that we have listed above. We’ve seen teachers track movement and/or verbal flow by filling in a chart every 5 or 10 minutes. If you record movement or verbal flow on an overhead transparency—one for each day of recording—in the space of a few days or weeks, you will have an amazing record in which you can see patterns emerging just by laying one transparency over another. ANECDOTAL RECORDS & TIME-SAMPLED OBSERVATIONS: We like to make notes in a spiral-bound or loose-leaf notebook—something that will lie flat. We write our notes on the right-hand page leaving the left-hand page blank. We’ve also worked with teachers who keep notes on sheets of sticky labels mounted on a clipboard. Later in the day or even a few days later, they paste them into a notebook on the right-hand page, of course. Later on, we come back to the notes and use the left-hand page as a place to reflect on the notes, making connections to other observations or to background reading that we’ve done, even developing theories about why some action is taking place. SAMPLES OF STUDENT WORK & DRAWINGS & PHOTOGRAPHS: Sometimes we will make a quick sketch of something—an activity, the way two kids were relating to one another. A sketch is like visual notes. It helps us to remember something and can be more descriptive than the words we could get down in the time it takes to make the sketch. The same is true of photographs. We love to take pictures of students at work, of activities in progress, even of stages of an activity. We generally encourage teachers to put both sketches and photographs in the same notebook that they use to record anecdotal records and time samples. Our reasoning is that like anecdotal records and time samples, these will later need a descriptive piece beside them, and they will also invite reflection and theory-building. Student work is just that—an artifact, a sample of an individual’s, small group’s, or entire class’ work collected over time. Depending on your question, both types of classroom artifacts can be very helpful data. Samples of student work can demonstrate individual or whole group progress. They can show you how students are making sense of concepts and how they are using them. INTERVIEWS & CONVERSATIONS: Interviews and conversations are great research tools. Formal interviews are those that you script for yourself prior to the interview—you ask the same questions of everyone to whom you talk and you ask these questions in the same order. Informal interviews are those that you quite literally enter into on the spur of the moment. Whichever you use (and you might use both), you will need to plan ahead. To prepare, especially for an informal interview or conversation, you need to really think about what you would want to learn about. Let’s go back to our example of the way kids interact with one another in the classroom. Say to yourself, “What if I bump into X? What does s/he know that would help me to better understand my group of kids?” It might be that you want to talk with the school’s social worker, or a teacher who had one of your students in a prior year. Whatever the connection, plan for it. If your focus is your students and their opinions or understandings, the same spirit of thoughtfulness is necessary. Surveys are great for getting information from a whole class or a large group. But be careful about the types of questions you ask and how many questions you ask. If you don’t want to have to develop ways of coding your data, don’t ask open-ended questions that invite thoughtful, often unanticipated answers. A sociogram is an analytical tool used to help you portray the social networks in your classroom. They are particularly useful if you’re trying to figure out how to change the interactive dynamic of the class. But they are also useful if you’re just trying to figure out how to group kids for instruction. To develop the data for a sociogram, you ask every child in your class the same three questions, for example, (1) If I were to form reading groups of four kids, who would you like to have in your group? (2) If I were to have four kids stay for lunch with me, who would you like to have in your group? (3) If you were a new student in the class, which three kids would you suggest I ask to help you learn the ropes? Questions can be asked orally but you need to record students’ answers so you have data to draw on as you begin to map their responses. We could say much more about sociograms but think you’ll learn more by looking at some good examples of sociograms in use by teachers. See Rachel Zindler’s study of a special ed inclusion class in New York City or Sarah Picard’s study of reading groups at www.teachersnetwork.org/tnli/research. You will also find lots of examples of surveys that teachers have developed at this web site. TEACHER RESEARCH JOURNALS: We feel that every teacher researcher should keep a research journal. Your research journal is like the best diary that ever was! It could have everything—the 10 minutes a day of writing that you are doing about your question, your notes from your anecdotal records, your reflections on those notes, your notes from background reading that you have done on your topic. It could, on the other hand, just be the place you record your thoughts about your research. Whatever, try to set it up so it really is a friendly place for you to write and so that it becomes precious to you. Do not leave it lying around in your classroom. This is where you think on paper. You want to keep it as a special place that you come to for special work on something that is of great importance to you. Okay—we’ve finished with the list of typical tools that are readily available to teachers. You can certainly add things like audiotaping or videotaping or even new ways to monitor interactions with kids via computers and the Internet, but unless you’re working with these media daily, just getting them ready to use can be a major production. So, we haven’t gone into them. However, we do have examples to recommend of teachers using them. As we’ve said before, see www.teachersnetwork.org. Matt Wayne’s video, “Fishbowl,” can give you a good idea of ways to engage a class in action research. Matt also has a study in the TNLI research section of the Teachers Network website that shows how he used audiotapes to monitor students’ progress as readers. Re: using the Internet in your classroom, the Teachers Network website has terrific curriculum units and lesson plans that engage kids interactively (see the Teachnet section of the website). Please Watch the following clips to get a description of some of the previous methods:

The seventh step of the process has to do with organizing and making sense of the data that you will be using in your classroom study. Frances Rust and Christopher Clark's guide to action research offers the following tips:

Analysis is the heart of making sense of your experience with action research. Analysis is fun and messy. It always begins with your data. Data never speak for themselves. Please remember this. Data never speak for

themselves. Your mind is the most important analytical tool that you have. Analysis is a process of telling a convincing story about the sense that your data led you to make. As well, you must persuade a skeptical audience that the story that you tell and the sense that you make are supported by evidence.

There are two major sources of support for your evidence:

- The first is the data you have collected and the patterns that you see.

- The second is equally important. It is what others have learned about this topic. If you haven’t already read other research and theory on your topic, now is the time to do it. This is critical to situating your work. If, for example, you find that the action you took has results that are very similar to those of other researchers, then you know your analysis is in the ballpark. Essentially, you can borrow from the authority of others that have come before you to strengthen the claims that you will make for the action that you took. If, however, your results contradict prior research, then you are well on the way to forming a provocative new question about why your study yielded such different results. You have something interesting to talk about with colleagues and with other researchers. Either way, what you learn locally can become part of a larger conversation among educators and researchers.

As you develop your analysis of data, here are the steps that you should follow:

Reporting on the results of your action:

- Describe the action(s) that you took.

- Reflect on the evidence you have collected.

- Count. Look for patterns.

- Share the evidence with colleagues.

- Examine what different explanations could explain the data

(draw on prior research). - Revisit assumptions about the children and the learning situation.

- Formulate a trial explanation.

- Develop an argument with evidence and claims.

- Check if your evidence support your claims: Does the evidence support your claims?; Do your colleagues (critical friends) find your argument credible?; How does the argument fit into ongoing debates and conversations?; What is unique about your setting or context?; Will others find your argument useful?

The following resources might be of help to better understand the way data analysis works in qualitative research studies:

Qualitative Data Analysis Software:

Please watch the following clip to better understand the different coding procedures that are traditionally used in qualitative research.

Guba (1981) proposes four criteria that should be considered by qualitative researchers in pursuit of trustworthiness:

a) Credibility (in preference to internal validity): One of the key criteria addressed by positivist researchers is that of internal validity, in which they seek to ensure that their study measures or tests what is actually intended. According to Merriam, the qualitative investigator’s equivalent concept, i.e. credibility, deals with the question,

“How congruent are the findings with reality?”

Some strategies to assure credibility are:

- Adoption of appropriate, well recognized research methods

- Triangulation via use of different methods, different informants, different sites, and moments.

- Tactics to help ensure honesty in informants

- Debriefing sessions between researchers

- Description of background, qualifications and experience of the researcher

- Member checks of data collected and interpretations/theories formed

- Thick description of phenomenon under scrutiny

- Examination of previous research to frame findings

b) Transferability (in preference to external validity/generalizability): External validity “is concerned with the extent to which the findings of one study can be applied to other situations”. In positivist work, the concern often lies in demonstrating that the results of the work at hand can be applied to a wider population. Since the findings of a qualitative project are specific to a small number of particular environments and individuals, it is difficult to demonstrate that the findings and conclusions are applicable to othersituations and populations. Because of that we use “Naturalistic Generalization” (Stake, 2005). Naturalistic generalization is a process where readers gain insight by reflecting on the details and descriptions presented in case studies. As readers recognize similarities in case study details and find descriptions that resonate with their own experiences; they consider whether their situations are similar enough to warrant generalizations.

Naturalistic generalization invites readers to apply ideas from the natural and in-depth depictions presented in case studies to personal contexts.

Some strategies to assure Transferability are:

-Provision of background data to establish context of study and detailed description of phenomenon in question to allow comparisons to be made

c) Dependability (in preference to reliability): In addressing the issue of reliability, the positivist employs techniques to show that, if the work

were repeated, in the same context, with the same methods and with the same participants, similar results would be obtained.

In order to address dependability in Qualitative research, the processes within the study should be reported in detail, thereby enabling a future researcher to repeat the work, if not necessarily to gain the same results. Thus, the research design may be viewed as a detailed “prototype model”.

Some strategies to assure Dependability are:

-Employment of “overlapping methods”

-In-depth methodological description to allow study to be repeated

d) Confirmability (in preference to objectivity): Objectivity in science is associated with the use of instruments that are not dependent on human skill and perception.The concept of confirmability is the qualitative investigator’s comparable concern to objectivity. Here steps must be taken to help ensure as far as possible that the work’s findings are the result of the experiences and ideas of the informants, rather than the characteristics and

preferences of the researcher.

Some strategies to assure Confirmability are:

-Triangulation to reduce effect of investigator bias

-Admission of researcher’s beliefs and assumptions

-Recognition of defects in study’s methods and their potential effects

-In-depth methodological description to allow integrity of research results to be scrutinized

-Use of diagrams to demonstrate “audit trail”

Resources:

The following article addresses these issues really well:

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education For Information, 22(2), 63-75.

- And here it is the reference to Guba´s work: E.G. Guba, Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries, Educational Communication and Technology Journal 29 (1981), 75–91.

The term “ethics” derives from the Greek word “ethos” which means character. To engage with the ethical dimension of your research requires asking yourself several important questions:

- What moral principles guide your research?

- How do ethical issues enter into your selection of a research problem?

- How do ethical issues affect how you conduct your research—the design of your study, your sampling procedure, etc.?

- What responsibility do you have toward your research subjects? For example, do you have their informed consent to participate in your project?

- What ethical issues/dilemmas might come into play in deciding what research findings you publish?

- Will your research directly benefit those who participated in the study?

The major principles associated with ethical conduct are (Litchman, 2011):

1- Do No Harm:

- It is the cornerstone of ethical conduct

- There should be a reasonable expectation by those participating in a research study that they will not be involved in any situation in which they might be harmed.

- Often applied to studies involving drugs or a treatment that might be harmful to participants

- The 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment, in which students played the role of guards and prisoners, is one example. When it was found that the guards became increasingly sadistic, the study was terminated.

- Recommendation: It is best to safeguard against doing anything that will harm the participants in your study. If you begin a study and you find that some of your participants seem to have adverse reactions, it is best to discontinue the study, even if it means foregoing your research plan.

2- Privacy and Anonymity:

- Any individual participating in a research study has a reasonable expectation that privacy will be guaranteed. Consequently, no identifying information about the individual should be revealed in written or other communication. Further, any group or organization participating in a research study has a reasonable expectation that its identity will not be revealed.

- Recommendation: Remove identifying information from your records. Seek permission from the participants if you wish to make public information that might reveal who they are or who the organization is. Use caution in publishing long verbatim quotes, especially if they are damaging to the organization or people in it. Often, these quotes can be located on the Internet and traced to the speaker or author.

3- Confidentiality:

- Any individual participating in a research study has a reasonable expectation that information provided to the researcher will be treated in a confidential manner. Consequently, the participant is entitled to expect that such information will not be given to anyone else.

- Recommendation: It is our responsibility to keep the information you learn confidential. If you sense that an individual is in an emergency situation, you might decide that you can waive your promise for the good of the individual or of others. You need to be much more sensitive to information that you obtain from minors and others who might be in a vulnerable position.

4- Informed Consent:

- Individuals participating in a research study have a reasonable expectation that they will be informed of the nature of the study and may choose whether or not to participate. They also have a reasonable expectation that they will not be coerced into participation.

- Recommendation: Our responsibility is to make sure that participants are informed, to the extent possible, about the nature of your study. Even though it is not always possible to describe the direction your study might take, it is your responsibility to do the best you can to provide complete information. If participants decide to withdraw from the study, they should not feel penalized for so doing. You need to be aware of special problems when you study people online. For example, one concern might be vulnerability of group participants. Another is the level of intrusiveness of the researcher.

5- Rapport and Friendship:

- Once participants agree to be part of a study, the researcher develops rapport in order to get them to disclose information.

- Recommendation: Researchers should make sure that they provide an environment that is trustworthy. At the same time, they need to be sensitive to the power that they hold over participants. Researchers need to avoid setting up a situation in which participants think they are friends with the researcher.

6- Intrusiveness:

- Individuals participating in a research study have a reasonable expectation that the conduct of the researcher will not be excessively intrusive. Intrusiveness can mean intruding on their time, intruding on their space, and intruding on their personal lives. As you design a research study, you ought to be able to make a reasonable estimate of the amount of time participation will take.

- Recommendation: Experience and caution are the watchwords. You might find it difficult to shift roles to neutral researcher, especially if your field is counseling or a related helping profession.

7- Inappropriate Behavior:

- Individuals participating in a research study have a reasonable expectation that the researcher will not engage in conduct of a personal or sexual nature.

- Here, researchers might find themselves getting too close to the participants and blurring boundaries between themselves and others. We probably all know what we mean by inappropriate behavior. We know it should be avoided

- Recommendation: If you think you are getting too close to those you are studying, you probably are. Back off and remember that you are a researcher and bound by your code of conduct to treat those you study with respect.

8- Data Interpretation:

- A researcher is expected to analyze data in a manner that avoids misstatements, misinterpretations, or fraudulent analysis. The other principles discussed involve your interaction with individuals in your study. This principle represents something different. It guides you to use your data to fairly represent what you see and hear. Of course, your own lens will influence you.

- Recommendation: You have a responsibility to interpret your data and present evidence so that others can decide to what extent your interpretation is believable.

9- Data Ownership and Rewards:

- In general, the researcher owns the work generated. Some researchers choose to archive data and make them available through databanks. Questions have been raised as to who actually owns such data. Some have questioned whether the participants should share in the financial rewards of publishing. Several ethnographers have shared a portion of their royalties with participants.

- Recommendation: In fact, most researchers do not benefit financially from their writing. It is rare that your work will turn into a bestseller or even be published outside your university. But, if you have a winner on hand, you might think about sharing some of the financial benefits with others.

This link will take you to an easy to use tool based on a form, that will assist you in generating a visual representation of the key elements of your study