The main research traditions in qualitative research are Narrative Research, phenomenology, ethnography, grounded theory, action research, and case study. You can find a detailed description of them in the tabs above.

Narrative Inquiry is a form of qualitative research that deals with the analysis of human experience, more specifically "it studies the lives of individuals and asks one or more individuals to provide stories about their lives. This information is then retold or restoried by the researcher into a narrative chronology" (Clandinin & Connellly, 2000).

It can be understood as "the transdisciplinary study of the activities involved in the generation and analysis of stories of life experiences (for example, life stories, narrative interviews, magazines, diaries, memoirs, autobiographies, biographies) and the presentation of reports adapted to this type of research " (Schwandt, 2007, p.204).

Other authors such as Creswell (2013) also define it as "a research tradition in which the narrative is understood as a spoken or written text that accounts for an event, action or a series of events and / or actions, connect-two in chronological order ". It is convenient at this point to clarify that although the use of narrative texts, stories and vignettes is a fundamental strategy for most research traditions, in this case we refer to narrative research as a particular form of research with characteristics and own procedures . In this way and despite the fact that "narratives can be both a method of study and the phenomenon of study itself" (Pinnegar & Daynes, 2007), we will only focus on the first ones. Narrative Inquiry emerged in the decade of the nineties of the last century and has its roots in literature, history, anthropology, sociology, sociolinguistics, and education; different fields of study that have also adopted their own approaches within this tradition of naturalistic research (Chase, 2005).

This type of research has been supported by the turn towards narrative and autobiography that has taken place in the social sciences, the result of postmodernist thinking and the lack of faith in the traditional discourses of the positivist paradigm. This new paradigmatic situation, described as the era of "blurred genres" (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994), arose as a response in the 70s and 80s to a variety of paradigms, theories, methods and research strategies , that from a criticism of faith to positivism advocated more interpretative-naturalist approaches for the study of social phenomena.

In narrative inquiry stories constitute the fundamental data for the researcher, which have come to be called "field texts". Usually these are collected through interviews and conversations that are then used to generate detailed portraits of the informants, in order to document their voices in a certain social and cultural framework.

Generally, the researcher compiles the stories of his informants, between one and five, and then "re-story" them (Creswell, 2013, p.74) according to a series of themes that emerge from them. The new story / narrative generated by the researcher can be structured around a chronology of events that describe the person's past, present and future experiences, always located within a specific socio-cultural context or context.

When putting into practice a narrative study it is convenient to follow a series of steps that under our point of view are masterfully summarized by John Creswell (2013) in the following way:

1. Determine if the research problem fits the characteristics of narrative research: it is advisable to use this research tradition when we intend to capture the detailed stories or life experiences of a single person or the experiences of a small number of individuals.

2. Review of the literature: Narrative researcher place in the foreground the experiences of the participants and relegate to the background the academic literature related to the research topic. They generally find the underlying direction and structure of their research reports in the participants' history rather than through a formal review of the literature.

3. Select between one and five informants with interesting stories and life experiences around the topic of research: Narrative researchers usually spend extended periods with their informants in order to capture their stories in their own words. For this they collect information in multiple formats (field texts, field notes, letters, photographs, videos, artifacts created by informants, etc.).

4. Collect information about the context of the informants' stories: It is vitally important to situate the stories within the personal experiences of the participants in their work, family, cultural, political and historical environment.

5. Analyze the stories of the informants in depth: The narrative researcher must generate a process of detailed analysis of the stories of their informants to later be able to "chronicle" them around a set of topics that make sense within the proposed study.

6. Verify the accuracy of the narrative report generated: Although John Creswell does not include this last step among his specific recommendations for the implementation of narrative research, we have considered it appropriate to include it as a final stage since it is of vital importance for the credibility of a study of these characteristics. The triangulation of data and the processes of checking with the informants (member checking) the consistency of the information shared with the researcher, are crucial to adequately represent the voices and life experiences of the informants.

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what narrative Inquiry is:

You can generate a visual representation of your narrative study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

A phenomenological study describes the meaning of the experiences lived by a person or group of individuals regarding a certain concept or phenomenon. For example, a research focused on the study of how a group of young people have experienced "Bullying" in secondary education, could be phenomenological if we focus our attention in the analysis of the common aspects experienced by them. Like the rest of the research traditions within the qualitative approach, phenomenology is not ultimately interested in explanation, but in reaching a deep understanding of a phenomenon from the eyes (frame of reference) of the person who has experienced it.

When designing a phenomenological (trascendental) qualitative study, the main steps to follow according to Moustakas (1994) are:

a) In the first place, the researcher must ask himself if his object of study really constitutes a phenomenon that can be investigated from this research tradition. As we anticipated earlier, this particular form of research focuses on understanding the way in which a group of individuals have experienced a certain phenomenon. The central thing will be, therefore, what their experiences have in common, not the personal history of each one as it would happen in a narrative investigation.

b) Secondly, the researcher must describe in depth the phenomenon that will focus the study.

c) Third, the researcher must submit his preconceptions about the phenomenon under study to a suspension process or "Bracketing" called "epoche." For this, the researcher must "suspend" his or her preconceived ideas about the phenomenon, to better understand it through the voices of the informants in his study.

d) In the data collection phase, the researcher generally develops in-depth interviews with a group of 7-12 participants who have experienced the phenomenon under. Usually the researcher opens the interview by asking two only questions to the interviewee: The first one related to their experience of the phenomenon; and the second related to the contexts and previous lived situations that he considers have affected him to experience the phenomenon under study, in the way he has done it.

e) In the data analysis phase, the researcher proceeds to the identification of dimensions or units of meaning that emerge from the in-depth interviews; these units are transformed into "clusters" of meanings, expressed in the form of psychological and phenomenological concepts. Finally, these transformations lead to a general description of the experience, the "textual description" of what the participants experienced and the "structural description" of how the phenomenon under study was experienced. Subsequently, starting from the "structural description," the researcher generates a composite description, called "essential" that brings together the essence of the phenomenon or invariant structure. This is derived from the common experiences described by the participants, making clear the underlying structure of the faith-phenomenon under study.

The following clip describes well what phenomenological studies are:

You can generate a visual representation of your phenomenological study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

Ethnography is a research tradition widely used in the social sciences that arises from cultural anthropology and qualitative sociology. We speak of ethnographic research or simply of ethnography, to allude both to the research process by which one inquires, learns and reflects on the way of life of a certain social group, as well as the final product (ethnographic portrait) of that research.

Hammersley and Atkinson (2007) define ethnography as the study of social interactions, behaviors, and perceptions that occur within social groups, teams, organizations, and communities. Therefore, the ultimate goal of this tradition is the analysis and detailed understanding of the particularities of a given social group. Due largely to this last aspect (the study of the particularities of a social group), we see that in some qualitative research manuals, the terms ethnography and case studies have been used indistinctly. From our point of view, there is a great conceptual difference between these two research traditions.

In ethnography, the researcher uses a macroscopic approach to study the social norms, rituals and perceptions of a particular social group; while in case studies the researcher uses a microscopic approach, based on the analysis of the singularity and uniqueness of the actions developed by the participants of a system with clearly defined limits.

A particular type of ethnography is the so-called school ethnography (Erickson, 1973). Although we can not directly apply all the approaches that govern traditional ethnography to school, we can establish certain parallelisms that allow us to use this tradition for the study of educational problems. Regardless of whether we want to conduct an ethnographic study on the performance of a group of teachers or students; or even a curriculum, we must understand the school context as a small social community with specific norms, rituals, values and beliefs.

Although all ethnographic studies must evolve and adapt to the demands that emerge from the field, it is important to define the main steps we can take when developing an ethnographic study. Creswell (2013) establishes the following:

a) First we must determine if ethnography is the most appropriate research tradition to study our research topic. We can use an ethnographic design if, as we said before, we are interested in describing and understanding the culture of a certain social group, its beliefs, its language, the rituals of its members, their behaviors. In the specific case of school ethnography, we will refer, therefore, to studies in which we intend to analyze, for example, the reasons why an educational center is innovative, or even the impact that the collaboration culture of a school has that they can successfully develop a learning community.

b) In the second place we must identify a social group with a shared culture that allows us to study it in detail (i.e. an educational center, an association to help relatives of people with disabilities, a sports team, a neighborhood action group, etc.). The ethnographic study will be more feasible if the members of the social group have lived together for a prolonged period of time, so that their shared language, behavior patterns and attitudes are identifiable.

c) When planning our study following this tradition of research, we must select subjects that embrace the analysis of the culture shared by its members. Some examples of topics that could be analyzed under the umbrella of ethnography are: the study of enculturation processes, the socialization processes of children and young people, the way in which they learn, the analysis of inequality, etc.

d) Subsequently we must collect information in the places where the group develops as such. In the spaces where its members work, live and interact on a daily basis.

e) Finally, we must analyze the data collected in a holistic way, trying to identify defining features and cultural patterns that help us understand the functioning of the group under study.

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what an ethnographical study is:

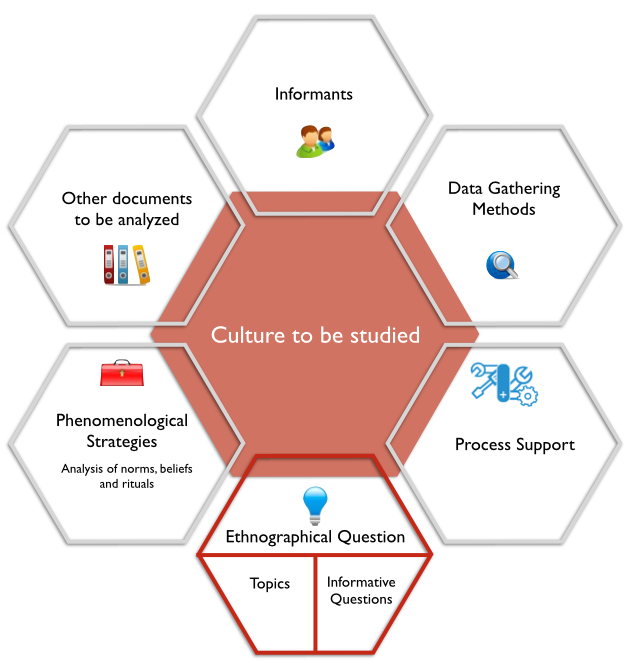

You can generate a visual representation of your ethnographical study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

Grounded Theory is a research tradition strongly influenced by symbolic interactionism, which was raised and developed by the sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). This, unlike those presented previously, offers the possibility for the researcher to generate theory through a systematic process of data collection and analysis. This tradition of research assumes that the behaviors that occur naturally in social contexts can be better analyzed from the generation of "bottom-up" categories and concepts. Glasser and Strauss (1967) define GT "as the discovery of theories from data systematically obtained from social research." Grounded Theory was initially developed in the nursing school of the University of California in San Francisco, with the aim of generating theories that supported the studies on the awareness of the proximity of his death, had patients in terminal state .

Glasser and Strauss proposed an innovative methodology that would help them investigate a topic that had not been previously investigated. As we mentioned earlier, his new methodological proposal was rooted in symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969).

According to symbolic interactionism, the meaning of a certain behavior is formed from social interaction. Therefore, this line of thought emphasizes the importance of meaning and interpretation as essential human processes. People create shared meanings through their social interactions, which will later define their reality. GT is very effective at exploring in a holistic way, both the relationships of a particular social group and the behavior of its members, insofar as they affect the life of the individual.

Grounded theory is especially recommended for the study of situations, phenomena and contexts that have not been studied enough, and on which there is not enough literature. Its essential characteristic is that theoretical propositions are not postulated as in other research traditions at the beginning of the study, but that generalizations emerge from the data themselves and not prior to the collection of them. Therefore, theories are constructed on the basis of interaction, fundamentally based on the actions, interactions and social processes that take place between people. Charmaz (2006) proposes the following phases for the implementation of the Grounded Theory:

1. Identification of our area of substantive interest: As it happens in the research traditions previously shown, a study based on GT must also start from the identification of an area of interest and research topic. In the case of this tradition, the selection of the area of interest and the specific topic of research, as well as relying on the personal interests of the researcher, must be based on the identification of an area whose theoretical development has not been satisfactorily covered in the literature. The identification of a theoretical "gap" will provide us with the starting point for the definition of our research design. However, unlike what happens in the rest of the research traditions, at this time we should not conduct a formal review of literature, just an initial screening that allows us to identify the aforementioned lack of theoretical support of the topic that we wish to study.

2. Data collection: As established by (Charmaz, 2006, Strauss & Corbin, 1990) the fundamental techniques of data collection in GT are observations, interviews, document analysis, and in some cases, even the collection of quantitative data from, for example, the completion of questionnaires, the use of social networks or even formal techniques of discourse analysis. The decisions regarding the data collection techniques to be used will be strongly directed by the informants included in our study. Both the data collection techniques and the informants will determine the quality and completeness of the emerging theory of the process. Strauss and Corbin (1990) offer the following recommendations in this regard: a) The context, group and / or individuals to be studied should be chosen on the basis of the main research question; b) The types of data collection techniques that will be used should be chosen according to their convenience to capture the information that we seek to generate our theory; c) In the case of longitudinal studies, it is necessary to make a decision about whether to follow an individual throughout the process, or certain individuals at different points in the process.

3. Open coding and axial coding of data: As we mentioned before, when we carry out a GT study, the data collection and analysis happen simultaneously. The first step in the analysis is based on data coding. Holton (2007) identifies two fundamental types of coding; the substantive (substantive coding) and the theoretical (theoretical coding). The substantive coding aims to conceptualize the empirical substance of the studied topic, that is, to help us analyze the data in which the theory is submerged (grounded). On the other hand, the theoretical coding helps us conceptualize the way in which the substantive codes are related to each other and are integrated to form our emerging theory. Strauss & Corbin (1990) identify three fundamental types of substantive coding: open coding, axial coding and selective coding. Open coding consists of scrutinizing the data (usually texts) by separating them into units of content, or codes, in order to identify concepts, ideas and meanings contained therein. The meticulous examination of the data allows us to identify, and what is more important, to conceptualize meanings in the analyzed texts. To implement this coding strategy, we must examine, segment and compare the data in relation to their similarities and differences. For this, the researcher conscientiously reads the texts under analysis and identifies portions of them that point out ideas, concepts and / or meanings, relevant for the understanding and conceptualization of the topic subject of study. The codes generated from the researcher's interpretation are called "open," while those that come from textual phrases mentioned by our informants (in an interview, for example) are called "in vivo." At the end of an open coding process we will obtain a list, generally extensive, of codes that, when compared and reduced among them, will allow us to obtain a classification of the second degree, composed of the so-called analysis categories (San Martín, 2014). Once the process of open encoding of our data has been concluded, and having obtained a set of categories of analysis, we will proceed to the axial coding. Through axial coding, the researcher identifies possible relationships between the categories obtained in the open coding, grouping them and / or sub-dividing them into sub-categories, as appropriate.

4. Production of "memos": During the open coding and the axial coding of the data, the researcher must annotate in an organized way the decisions that he is taking, as well as the abstractions that he generates. The so-called "memos" are notes that researchers generate as they codify the data, which allows a written record of abstract thinking when creating codes and categories. Strauss and Corbin (1990, p.197) define them as "written records of analysis." The generation of memos is essential in GT because it constitutes a process of reflection by which researchers interpret the data in an analytical manner in order to discover emerging patterns that help develop the sought after substantive theory.

5. Selective coding of data: As mentioned previously, the third type of substantive coding is the so-called selective coding. It occurs as an extension of the axial coding, characterized by a higher level of abstraction. This third coding process is intended to help the researcher identify what the authors of the grounded theory call the "core category." This allows the researcher to express the phenomenon of research through the integration of the categories and sub-categories of open and axial coding. The central category that results from a selective coding process must group the categories in the axial coding phase, in order to explain the phenomenon or phenomena studied in our research.

6. Search for abstract theoretical codes: In parallel to the realization of axial and selective coding, the researcher must also begin to develop what is called "theoretical coding." Unlike the three procedures of substantive coding previously described, in the theoretical coding the researcher tries to identify a series of theoretical codes that allow him to develop an integrated and explanatory substantive theory of the phenomenon object of study. A theoretical code consists of the relational model through which all previously identified codes and substantive categories are related to the central category.

7. Review of the literature: Until now, it is not recommended to carry out an exhaustive review of the literature related to the phenomenon under study. This should be done around the category or central categories emanated from the previous phase. It is in this moment of the investigation when the existing literature in the field will allow us to generate our emergent or substantive theory.

8. Generation of the emerging theory and its integration with preexisting knowledge: GT focuses on the generation of what is called "substantive theory." This differs from formal theory, of a universal nature, in that the substantive theory deals with a type of theoretical construction of inductive order, which allows us to understand singular social realities. The substantive theory is generated from the dynamic analysis of data and therefore differs from the deductive and static nature involved in the processes of generation of formal theories. It is to this particular type of theory, to which we will refer in this eighth phase of the process of implementing a study supported by Grounded Theory.

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what Grounded Theory is:

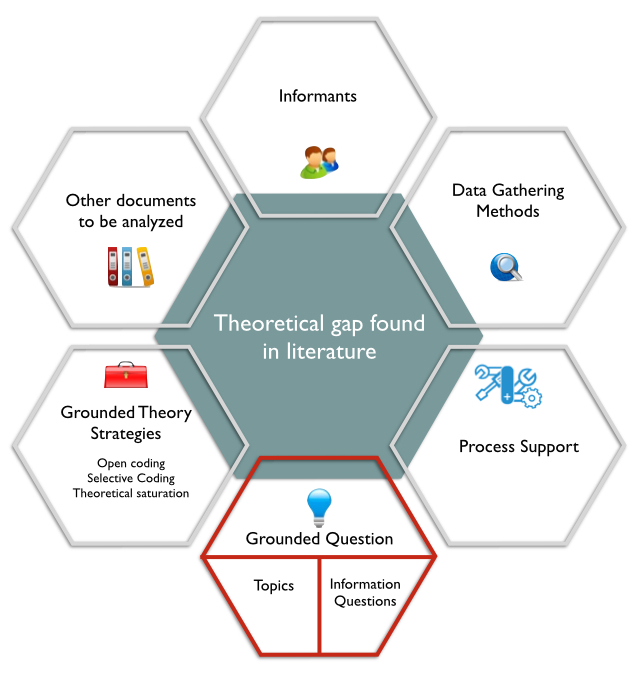

You can generate a visual representation of your Grounded Theory study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

Case Study is a research tradition that allows the in-depth analysis of particular social realities, or as MacDonald and Walker (1975) indicate, for the study of well-defined systems in action. This is a tradition that has been used since we have historical records (Flyvbjerg, 2011). However, case studies as we understand them today have their origins at the end of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, in interpretative studies carried out in anthropology, psychology, history and sociology (Simons, 2009).

The main definitions of this tradition reveal that a case study, as proposes by (Rodríguez Gómez et al., 1999), implies a process of inquiry characterized by detailed, comprehensive, systematic and in-depth examination of the case under study. However there are many approaches to this tradition of research.

Yazan (2016) states that the three most relevant case study approaches in the social sciences have been proposed by Robert Yin, Sharan Merriam and Robert Stake. The three approaches differ fundamentally in the worldview or paradigmatic position from which they were conceived, as well as in the practical procedures they propose. Yin makes his proposal from a positivist position, while Merriam and Stake propose their models from constructivistic conceptions that align better with qualitative studies. Therefore, from this moment we opted for the existentialist model proposed by Stake (1995) since we consider that it has had the greater impact in the social sciences, perhaps because of the refinement of its proposal and its recommendations of practical application .

For Stake (1995), a case study should allow us to understand in depth and holistically, empirically, empathically and interpretively the person, innovation or program object of study. To do so, the researcher should focus on the observable actions of the informants that are part of the case, instead of analyzing their perceptions of attitudes and beliefs. These research design follows a progressive approach (progressive in focus) so they are flexible and they adapt to the problems and tensions identified by the informants as the study evolves. Despite the widespread belief that this type of studies do not allow the researcher to generalize their results, it does facilitate a particular type of generalization called naturalistic (Stake, 1998). The in-depth study of particular situations clearly delimited, allows that third parties in similar contexts can learn from the conclusions obtained in a specific case study.

It is important to distinguish the typology of the case object of our study in order to design it properly, and always keep in mind the ultimate objective with which we study it. Stake (1995) identifies three types of case studies depending on the purpose of the study:

a) Intrinsic case study: The intrinsic case study is conducted to learn about a unique phenomenon which the study focuses on. The researcher needs to be able to define the uniqueness of this phenomenon which distinguishes it from all others; possibly based on a collection of features or the sequence of events.

b) Instrumental case study: The instrumental case study is done to provide a general understanding of a phenomenon using a particular case. The case chosen can be a typical case although an unusual case may help illustrate matters overlooked in a typical case because they are subtler there.

c) Multiple case study: The collective case study is done to provide a general understanding using a number of instrumental case studies that either occur on the same site or come from multiple sites.

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what a Case Study is:

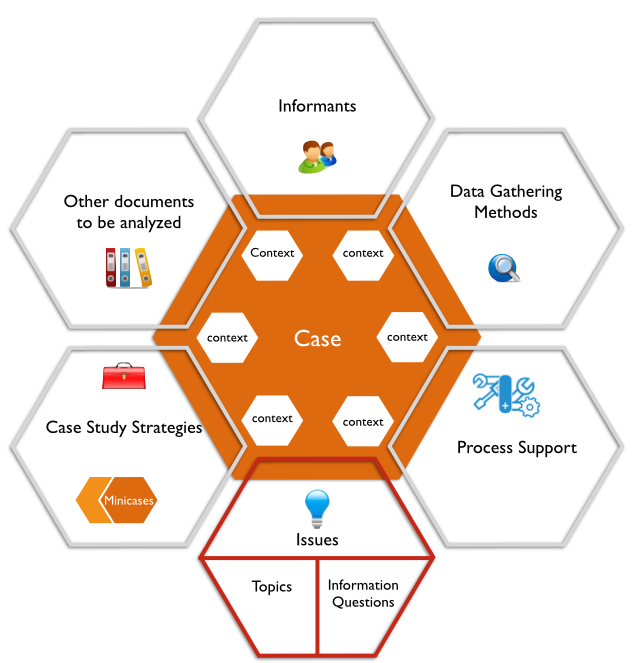

You can generate a visual representation of your Case Study study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

Action research (A-R) is the research tradition most oriented to the educational practice of the six presented by Hopscotch. From this tradition, the essential purpose of the research is not the accumulation of knowledge about teaching-learning, or the understanding of the educational reality, but, fundamentally, to provide information that guides a decision-making process and the innovation and change processes for the improvement of a given reality or issue. Therefore, the main goal of action research is to improve the practice instead of generating knowledge about it (Elliott, 1993).

Berg (2001) raises the existence of three fundamental types of action research: a) Technical Action Research; b) Practical Action Research, and e; c) Emancipatory Action Research. Each of them presents a different goal and it is based on a different worldview. Technical Action Research aims to "prove a particular intervention / innovation based on a specific theoretical framework" (p.186). Supported therefore in post-positivist explanatory positions. Practical Research-Action, on the other hand, "seeks to improve practice" (p.186), thus sustaining itself in an interpretive position that allows the discovery of social meanings. Finally, the emancipatory or critical Action Research has as the essential objective of social, political or personal change; its roots can be found in a transformative paradigmatic position. Currently, practical and emancipatory A-R predominate, thus framing a large percentage of the studies supported by this research tradition in the interpretative and critical paradigms (transformative Cosmovision).

However, and from our point of view, the emancipatory / critical A-R constitutes the approach that we understand should govern the studies carried out by and for teachers. We believe that a teacher should not only face a practical problem in the classroom, but should face the study of that problem from a social perspective that might help him to better understand its origins and structure, thus favoring a social change in the end.

Within the emancipatory/critical A-R, we also found participatory A-R (Kemmis and McTaggart, 2005). It is a form of Action Research that differs from conventional research in three ways. First, it focuses on research whose objective is to allow and promote action. This is achieved through a reflection cycle, through which participants collect and analyze the data, to later decide what action should be followed to improve the practice. The resulting action is then re-investigated in an iterative reflective cycle that perpetuates data collection, reflection and action. Second, participatory A-R pays close attention to power relations, advocating that power be shared deliberately between the researcher and the researched. Third, participatory A-R contrasts with less dynamic approaches and argues that those being investigated should actively participate in the process. Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) specify some of the characteristics of this particular form of A-R:

a) It constitutes a social process: participative A-R studies the relationship between the individual and the social sphere of any phenomenon under study. As we mentioned earlier, when a teacher investigates his own practice, he does it by understanding it as an educational process that has close relationships with the prevailing social model.

b) It is participatory: participatory A-R promotes that people examine their knowledge and the way in which they interpret themselves and their actionS in the surrounding social context. It is therefore participative since we can only conduct A-R about ourselves, as individuals or as a collective.

c) It is practical and collaborative: participatory A-R encourages people to examine social practices (communication, production and social organization) that relate them to other people in social interactions.

d) It is emancipatory: participatory A-R allows people to free themselves from the constraints imposed by social structures that limit their self-development and self-determination.

e) It is critical: participatory A-R helps people to free themselves from the constraints generated by social media, through which they interact.

f) It is reflexive: participatory A-R investigates the reality to change it, and changes the reality to investigate it. That is, it proposes a constant cyclical process of questioning and transforming people's practices through a cycle of critical and self-critical analysis, action and reflection.

g) It transforms theory and practice: participatory A-R aims to articulate and develop both theory and practice through a process of reflection and criticism about them. Therefore, it involves addressing daily practice from the people involved in it, to "explore the potential of different perspectives, theories and discourses that help illuminate particular practices and practical situations, as a basis for the development of critical understandings and ideas on how Things must be transformed. " (Kemmis and McTaggart, 2005, p.568).

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what Action Research is:

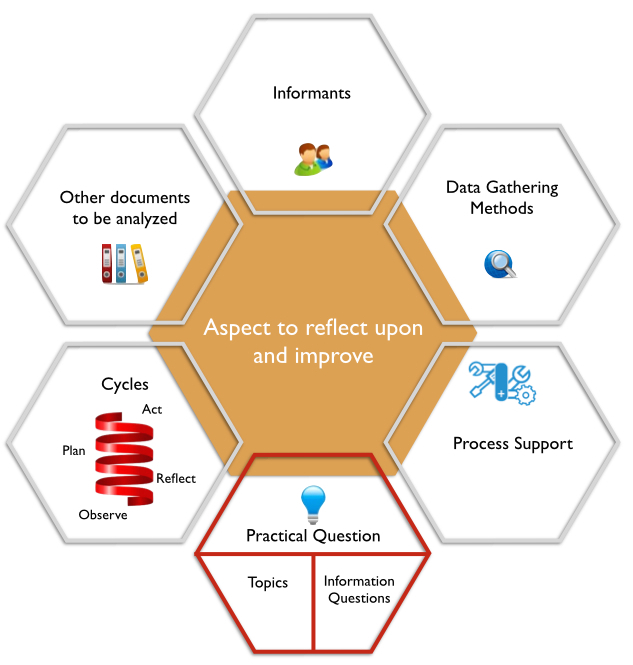

You can generate a visual representation of your Action Research study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

Phenomenography, denotes a research tradition aiming at describing the different ways a group of people understand a phenomenon (Marton, 1981), whereas phenomenology, aims to clarify the structure and meaning of a phenomenon (Giorgi, 1999).This research tradition, aims at identifying and interrogating the range of different ways in which people perceive or experience specific phenomena (typically learning, teaching or aspects thereof).

References:

Online Resources:

Phenomenographic or phenomenological analysis: does it matter?

Making sense of ‘pure’ phenomenography in information and communication technology in education

The Concepts and Methods of Phenomenographic Research

The following clip summarizes what phenomenography is:

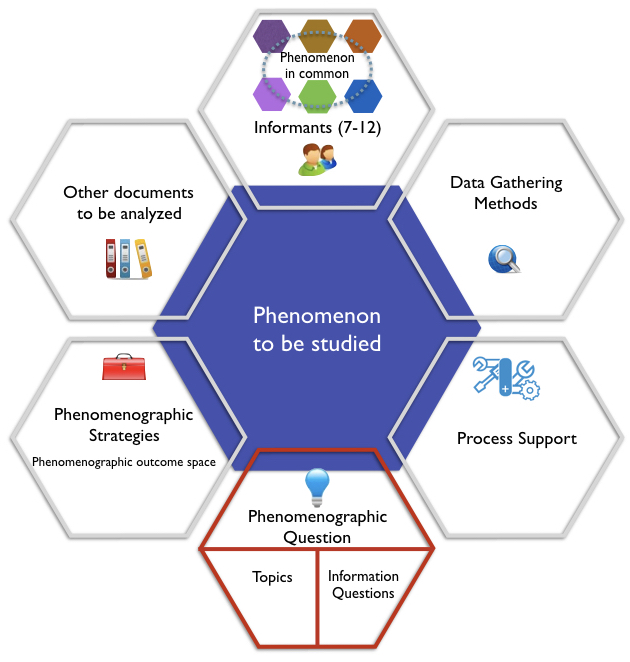

You can generate a visual representation of your phenomenography using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

Data analysis in Phenomenography: One key aspect of phenomenography has to do with the process of analyzing the data gathered. The main steps proposes by González (2010) and Khan (2014) are:

Step 1. Familiarization step: the transcripts will be read several times in order to become familiar with their contents. This step will correct any mistakes within the transcript.

Step 2. Compilation step: The second step will require a more focused reading in order to deduce similarities and differences from the transcripts. The primary aim of this step is to compile teachers’ answers to the certain questions that have been asked during interviews. Through this process, the researcher will identify the most valued elements in answers.

Step 3. Condensation step: This process will select extracts that seem to be relevant and meaningful for this study. The main aim of this step is to sift through and omit the irrelevant, redundant or unnecessary components within the transcript and consequently decipher the central elements of the participants’ answers.

Step 4. Preliminary grouping step: the fourth step will focus on locating and classifying similar answers into the preliminary groups. This preliminary group will be reviewed again to check whether any other groups show the same meaning under different headings. Thus, the analysis will present an initial list of categories of descriptions.

Step 5. Preliminary comparison of categories: this step will involve the revisions of the initial list of categories to bring forth a comparison among the preliminary listed categories. The main aim of this step is to set up boundaries among the categories. Before going through to the next step, the transcripts will be read again to check whether the preliminary established categories represent the accurate experience of the participants.

Step 6. Final outcome space: in the last step, the researcher hopes to discover the final outcome space based on their internal relationships and qualitatively different ways of understanding the particular phenomena. The phenomenographic outcome space describes the different ways, in which a phenomenon is experienced in a cohort. It also describes the different ways, in which a researcher has interpreted how a phenomenon is experienced in a cohort.

References:

González, C. (2010). What do university teachers think eLearning is good for in their teaching? Studies in Higher Education, 35(1), 61-78.

Khan, S. H. (2014). Phenomenography: A qualitative research methodology in Bangladesh. International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications, 5(2), p.p. 34- 43. http://www.ijonte.org/FileUpload/ks63207/File/04.khan.pdf

Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA, : Sage Publications Ltd.

The following tool will help you choose the research design (open in new window):