There are five main types of quantitative research designs: descriptive, correlational, pre-experimental, quasi-experimental and experimental. The differences between the four types primarily relates to the degree the researcher designs for control of the variables in the experiment. You an find a detailed description of them in the tabs above.

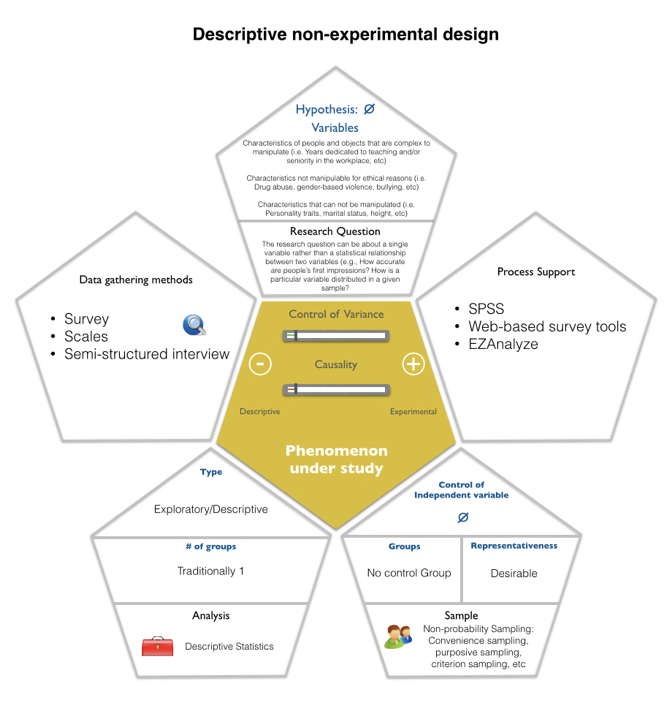

Descriptive designs are intended to describe an educational situation or reality and / or classify it in a certain category. They are very frequent in education and in general in the field of social sciences. Most of the descriptive studies are carried out through questionnaires or observations. Hence, the types of descriptive designs that can be carried out are survey-research and observational.

An example of descriptive design tries to answer the following question: what is the use of mobile phones by teenagers throughout the day? It is interesting to know the following variables: the daily time dedicated and the differential frequency of use of Whatsapp, social networks, and calls.

Survey-research: The main objective of a survey-research design is to describe features or characteristics of a group or population through the responses provided by the participants to a questionnaire or interview administered by the researcher. They seek to collect information referring to the entire population, and in cases where this is not possible, a sample that represents it. The main instruments in this type of design are questionnaires and structured or semi-structured interviews. The information collected through the questionnaires is usually of two types: a) sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, such as gender, profession, age, etc., and b) attitudes, opinions, perceptions, behaviors, habits, experiences, etc. Because the objective of these designs is to see the distribution of a certain variable -for example, the opinion of people over 65 years of age regarding the digitalization of the health system in Madrid- in the entire population -persons of 65 who live in Madrid-, it is vitally important that when this is not possible, a sample is selected through the probabilistic sampling procedures that allow to represent the population from which it has been extracted and thus generalize the results. In addition to the rigor in the selection of the sample, another of the decisive questions in this type of research is the validation of the instrument that will be used when it is prepared by the researcher.

Observational designs: Observation is defined by Martínez-González (2007) as the act of looking carefully at something without intervening in its natural course, with the intention of examining it, interpreting it and obtaining conclusions. The fact of being talking about observing, may introduce some confusion with the observation used in qualitative research. In this case, we are referring to an intentional, planned, structured observation, registered in an objective manner, and seeking the explanation of the observed phenomenon. That is, what is observed is quantified by different criteria such as frequency, intensity, domain, etc. One of the most complicated aspects of an intentional observation is the work that needs to be done to define what needs to be observed. For example, if we want to observe the attachment behavior of children with their teacher in early childhood education, we must explicitly and clearly specify which behaviors characterize each type of attachment in order to identify them when conducting an observation. It will also be necessary to determine if what matters is the appearance of the behavior, its frequency, or perhaps the registration of patterns of relationship between the teacher and the child. To carry out this process we have to be very sure that a certain behavior expresses what we want to measure. Hence the difficulty to observe internal aspects of the human being, which have a difficult manifestation sometimes to interpret, such as moods, thoughts or even emotions. As described in the case of survey-research studies, the measurements of an observational study can be carried out over time (longitudinal) or at a single moment (cross-sectional). The most frequently used observational designs can be found in the clinical field. The instruments for collecting observational information in a quantifiable way are observational codes, some of them already elaborated, validated and published for use in samples determined according to context and age. Control lists or estimation scales are also common.

You can use the following tool to generate a visual representation of a Descriptive non-experimental design:

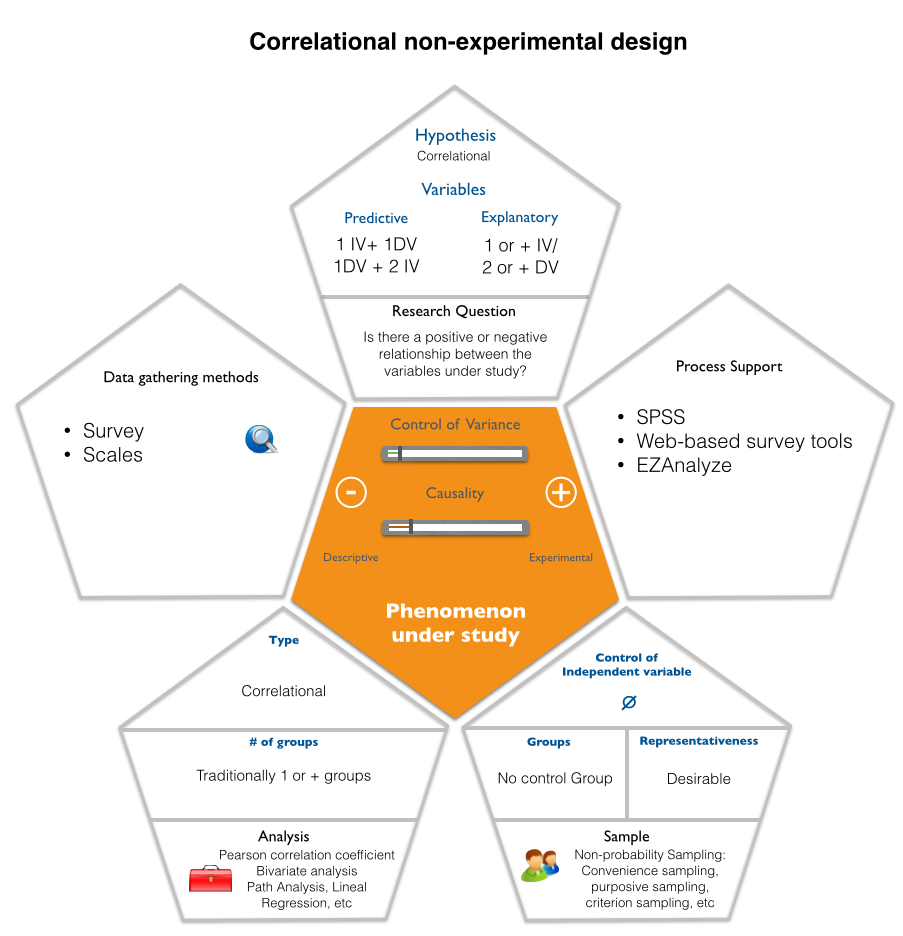

A Correlational Design explores the relationship between variables using statistical analyses. However, it does not look for cause and effect and therefore, is mostly observational in terms of data collection. A correlational study determines whether or not two variables are correlated. This means to study whether an increase or decrease in one variable corresponds to an increase or decrease in the other variable.

There are three types of correlations that are identified:

Positive correlation: Positive correlation between two variables is when an increase in one variable leads to an increase in the other and a decrease in one leads to a decrease in the other. For example, the amount of money that a person possesses might correlate positively with the number of cars he owns.

Negative correlation: Negative correlation is when an increase in one variable leads to a decrease in another and vice versa. For example, the level of education might correlate negatively with crime. This means if by some way the education level is improved in a country, it can lead to lower crime. Note that this doesn't mean that a lack of education causes crime. It could be, for example, that both lack of education and crime have a common reason: poverty.

No correlation: Two variables are uncorrelated when a change in one doesn't lead to a change in the other and vice versa. For example, among millionaires, happiness is found to be uncorrelated to money. This means an increase in money doesn't lead to happiness.

There are essentially two reasons that researchers interested in statistical relationships between variables would choose to conduct a correlational study rather than an experiment. The first is that they do not believe that the statistical relationship is a causal one. The second reason that researchers would choose to use a correlational study rather than an experiment is that the statistical relationship of interest is thought to be causal, but the researcher cannot manipulate the independent variable because it is impossible, impractical, or unethical.

The two main types of correlational designs are:

Explanatory Correlational Design: An explanatory design seeks to determine to what extent two or more variablesco-vary. Co-vary simply means the strength of the relationship of one variable to another. In general, two or more variables can have a strong, weak, or no relationship. This is determined by the product moment correlation coefficient, which is usually referred to as r. The r is measured on a scale of -1 to 1. The higher the absolute value the stronger the relationship.

Prediction Correlational Design: Prediction design has most of the same functions as explanatory design with a few minor changes. In prediction design, we normally do not use the term explanatory and response variable. Rather we have predictor and outcome variable as terms. This is because we are trying to predict and not explain. In research, there are many terms for independent and dependent variable and this is because different designs often use different terms.

You can use the following tool to generate a visual representation of your Correlational Design:

Pre-experiments are the simplest form of research design. In a pre-experiment either a single group or multiple groups are observed subsequent to some agent or treatment presumed to cause change.

Types of Pre-Experimental Design

One-shot case study design: A single group is studied at a single point in time after some treatment that is presumed to have caused change. The carefully studied single instance is compared to general expectations of what the case would have looked like had the treatment not occurred and to other events casually observed. No control or comparison group is employed.

One-group pretest-posttest design: A single case is observed at two time points, one before the treatment and one after the treatment. Changes in the outcome of interest are presumed to be the result of the intervention or treatment. No control or comparison group is employed.

Advantages of pre-experimental designs:

As exploratory approaches, pre-experiments can be a cost-effective way to discern whether a potential explanation is worthy of further investigation.

Disadvantages of pre-experimental designs:

Pre-experiments offer few advantages since it is often difficult or impossible to rule out alternative explanations. The nearly insurmountable threats to their validity are clearly the most important disadvantage of pre-experimental research designs.

You can use the following tool to generate a visual representation of your Pre-Experimental Design

Quasi-experimental designs examine cause-and-effect relationships between or among independent and dependent variables. However, one of the characteristics of true-experimental design is missing, typically the random assignment of subjects to groups. Although quasi-experimental designs are useful in testing the effectiveness of an intervention and are considered closer to natural settings, these research designs are exposed to a greater number of threats of internal and external validity, which may decrease confidence and generalization of study's findings.

Nonequivalent control group designs: The most common subset of quasi-experimental research designs are the nonequivalent control group designs. In one implementation of this design, subjects in the control group are intentionally matched by the researcher to subjects in the treatment group on characteristics which might be associated with the outcome of interest. This matching can be done at the individual level, resulting in a one-to-one match of individuals in the two groups. Another approach is aggregate matching, in which researchers select a control group with the same general composition of relevant characteristics (for example, the same proportion of females and the same age distribution) as the treatment group. These approaches are considered quasi-experimental due to the fact that assignment of subjects to groups is intentional and not random. Another common approach to this type of quasi-experimental research design is the use of existing groups. For example, a comparison could be made between students in two classrooms, with the stimulus administered in only one classroom.

Time-series data Designs: Another quasi-experimental approach involves time-series data, in which researchers observe one group of subjects repeatedly both before and after the administration of the treatment. This can be done in a controlled experimental setting, but this design also lends itself well to a more naturalistic setting in which data are commonly collected on a group of subjects and researchers are interested in the effects of some treatment or intervention which they did not experimentally apply. For example, researchers might examine the yearly test scores of students at a given school for several years both before and after the implementation of an extended school day; in this situation the yearly tests scores represent the time-series data and the change to an extended school day is the naturally occurring, quasi-experimental treatment. This approach is an improvement over the single pre-test/post-test design, which is unable to demonstrate long-term effects. The time-series data design can be further improved by including a control group which is also examined over time but which does not experience the treatment; such a design is termed a multiple time-series design.

While quasi-experimental designs are often more practical to implement than true experiments, they are more susceptible to threats to internal validity. Special care must be taken to address validity threats, and the use of additional data to rule out alternate explanations is advised.

You can use the following tool to generate a visual representation of your Quasi-experimental Design

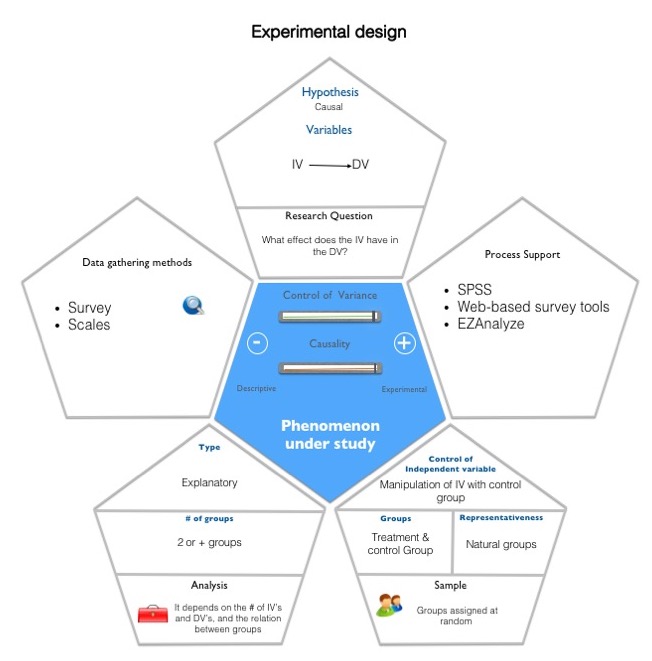

An experiment is a study in which the researcher manipulates the level of some independent variable and then measures the outcome. Experiments are powerful techniques for evaluating cause-and-effect relationships. Many researchers consider experiments the "gold standard" against which all other research designs should be judged. Experiments are conducted both in the laboratory and in real life situations.

True experiments, in which all the important factors that might affect the phenomena of interest are completely controlled, are the preferred design. Often, however, it is not possible or practical to control all the key factors, so it becomes necessary to implement a quasi-experimental research design.

In an experiment, the researcher manipulates the factor that is hypothesized to affect the outcome of interest. The factor that is being manipulated is typically referred to as the treatment or intervention. The researcher may manipulate whether research subjects receive a treatment and the level of treatment.

Example of true experiment: Suppose, for example, a group of researchers was interested in the causes of maternal employment. They might hypothesize that the provision of government-subsidized child care would promote such employment. They could then design an experiment in which some subjects would be provided the option of government-funded child care subsidies and others would not. The researchers might also manipulate the value of the child care subsidies in order to determine if higher subsidy values might result in different levels of maternal employment.

Random Assignment

-Study participants are randomly assigned to different treatment groups

-All participants have the same chance of being in a given condition

-Participants are assigned to either the group that receives the treatment, known as the "experimental group" or "treatment group," or to the group which does not receive the treatment, referred to as the "control group"

-Random assignment neutralizes factors other than the independent and dependent variables, making it possible to directly infer cause and effect

Random Sampling

-Traditionally, experimental researchers have used convenience sampling to select study participants. However, as research methods have become more rigorous, and the problems with generalizing from a convenience sample to the larger population have become more apparent, experimental researchers are increasingly turning to random sampling. In experimental policy research studies, participants are often randomly selected from program administrative databases and randomly assigned to the control or treatment groups.

Advantages of Experimental Designs

The environment in which the research takes place can often be carefully controlled. Consequently, it is easier to estimate the true effect of the variable of interest on the outcome of interest.

Disadvantages of Experimental Designs

It is often difficult to assure the external validity of the experiment, due to the frequently nonrandom selection processes and the artificial nature of the experimental context.

You an use the following tool to create your Experimental Design

| The following resources might also be of further help in order to decide the quantitative design that best fits the needs of your study: |