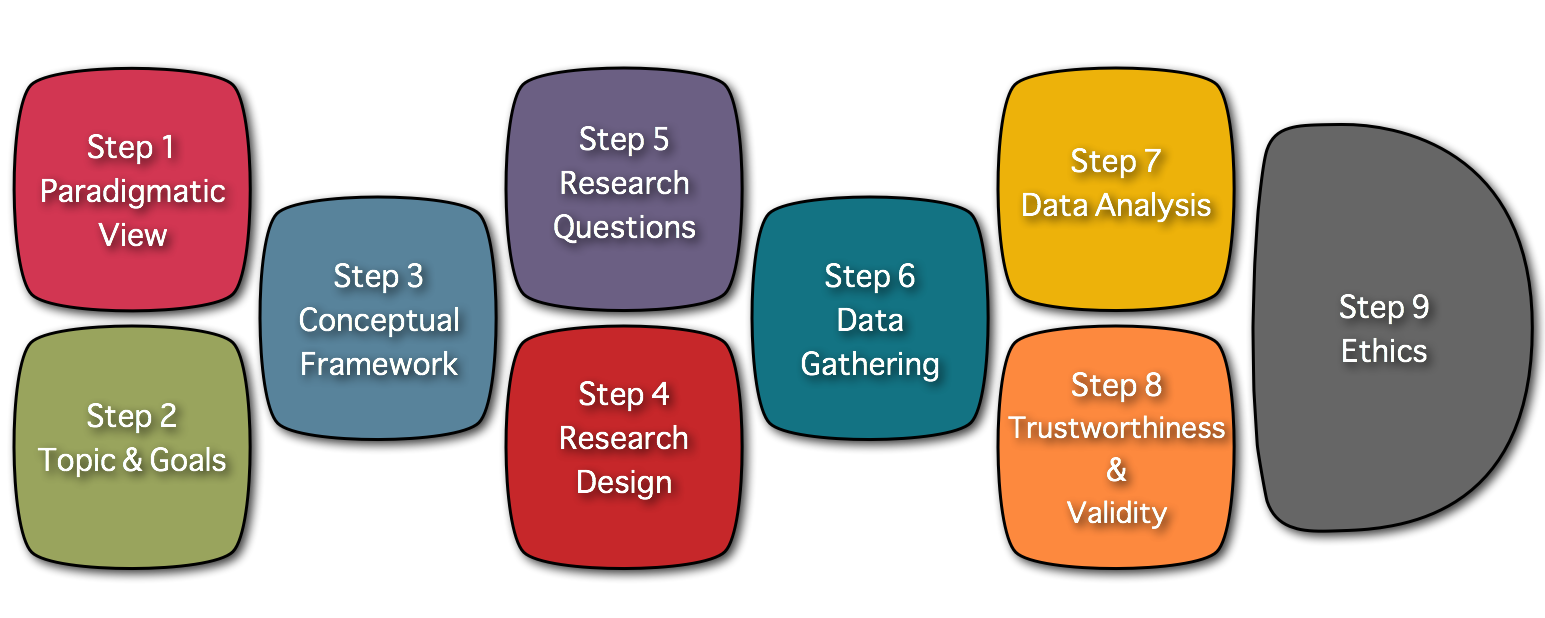

Steps of the Hopscotch Model (Inicial)

- Home /

- Steps of the Hopscotch Model (Inicial)

Qualitative researchers bring to their studies their particular way of understanding how things work in our world, and the way knowledge is constructed. The worldview of the researcher as well as his/her adscription to a particular Interpretive Community (if so) is going to have a deep impact in the decisions and inquiry procedures he/she will put in practice.

Guba (1990) describes a paradigm or worldview as "a basic set of beliefs that guide action.” That basic set of beliefs of the researcher is based on his ontological (What is the nature of reality?) and epistemological assumptions (What is the nature of knowledge and the relationship between the knower and the would-be known?). Therefore, how one views the constructs of social reality and knowledge affects how they will go about uncovering knowledge of relationships among phenomena and social behavior. Your ontological assumptions inform your epistemological assumptions which inform your methodology and these all give rise to your methods employed to collect data.

From an ontological point of view, post-positivism understands that there is one reality which is knowable within a specific level of probability, while constructivism understands that the nature of reality is multiple and socially constructed. Pragmatism asserts that there is a single reality and that all individuals have their own unique interpretation of reality. Finally, those following a transformative worldview reject cultural relativism and recognize that various versions of reality are based on social positioning.

From an epistemological point of view, post-positivists believe that objectivity is key and than the researcher manipulates and observes in a dispassionate objective manner. Constructivists on the contrary, believe that there should be an interactive link between researcher and participants, and that since knowledge is socially and historically situated, it needs to address issues of power and trust. Pragmatism on its side, understands that relationships in research are determined by what the researcher deems as appropriate to a particular given study. Finally, a transformative worldview acknowledges that since there is an interactive link between researcher and participants, and knowledge is socially and historically situated, there is a clear need to address issues of power and trust.

These ontological and epistemological assumptions have a direct impact in the methodology used in a given study. Post-positivism calls for interventionist quantitative studies, while constructivism prefers qualitative hermeneutical studies, and pragmatists matches methods to specific questions and purposes of research by using mixed methods. In the case of researchers following a transformative worldview, qualitative methods deeply grounded in critical theories, are the most common ones.

The main Worldviews (Creswell, 2013) are:

POST-POSITIVISM

- This tradition comes from 19th-century (Comte, Mill, Durkheim, Newton, and Locke).

- It represents the traditional form of research (scientific method).

- Called post-positivism since it represents the thinking after positivism, challenging the traditional notion of the absolute truth of knowledge (Phillips & Burbules, 2000).

- Postpositivists hold a deterministic philosophy in which causes (probably) determine effects or outcomes.

- It is reductionistic in that the intent is to reduce the ideas into a small, discrete set to test, such as the variables that comprise hypotheses and research questions. To test theories.

- The knowledge that develops through a postpositivist lens is based on empirical observation and measurement of the objective reality that exists “out there” in the world.

CONSTRUCTIVISM

- Based on the ideas of Mannheim and from works such as Berger and Luekmann’s (1967). The Social Construction of Reality and Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry.

- There is not one objective truth. Truth is socially constructed.

- Social constructivists believe that individuals seek understanding of the world in which they live and work, developing subjective meanings of their experiences.

- These meanings are varied and multiple, leading the researcher to look for the complexity of views rather than narrowing meanings into a few categories or ideas.

- The goal of the research is to rely as much as possible on the participants’ views of the situation being studied..

- The researcher’s intent is to make sense of (or interpret) the meanings others have about the world.

- Rather than starting with a theory (as in postpositivism), inquirers inductively develop a theory.

TRANSFORMATIVE

- This position arose during the 1980´s and 1990´s.

- It came from individuals who felt postpositivist assumptions imposed structural laws and theories that did not fit marginalized individuals.

- In the main, these inquirers felt that the constructivist stance did not go far enough in advocating for an action agenda to help marginalized peoples.

- It focuses on the needs of groups and individuals in our society that may be marginalized.

- Historically, the transformative writers have drawn on the works of Marx, Adorno, Marcuse, Habermas, and Freire.

- No uniform body of literature characterizing this worldview: Includes groups of researchers that are critical theorists; participatory action researchers; Marxists; feminists; racial and ethnic minorities; persons with disabilities; indigenous and postcolonial peoples; and members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans-sexual, and queer communities.

- This worldview holds that research inquiry needs to be intertwined with politics and a political change agenda to confront social oppression at whatever levels it occurs (Mertens, 2010).

PRAGMATISM

- Pragmatism derives from the work of Peirce, James, Mead, and Dewey.

- There are many forms of this philosophy, but for many, pragmatism as a worldview arises out of actions, situations, and consequences rather than antecedent conditions (as in postpositivism).

- Instead of focusing on methods, researchers emphasize the research problem and use all approaches available to understand the problem.

- Individual researchers have a freedom of choice. In this way, researchers are free to choose the methods, techniques, and procedures of research that best meet their needs and purposes.

- As a philosophical underpinning for mixed methods studies, Morgan (2007), Patton (1990), and Tashakkori and Teddlie (2010) convey its importance for focusing attention on the research problem in social science research and then using pluralistic approaches to derive knowledge about the problem.

Please watch the following clip to clarify the previous concepts:

Maxwell (2008) states that goals include motives, desires, and purposes—anything that leads you to do the study or that you hope to accomplish by doing it.)

Some questions that could help us to better define the goals of our study are:

- Why is your study worth doing?

- What issues do you want it to clarify, and what practices and policies do you want it to influence?

- Why do you want to conduct this study, and why should we care about the results?

According to (Maxwell, 2008), goals serve two main functions for your research:

- They help guide your other design decisions to ensure that your study is worth doing.

- They are essential to justifying your study, a key task of a funding or dissertation proposal.

There are three kinds of goals for doing a study (Maxwell, 2008):

- Personal goals: those that motivate you to do this study; they can include a desire to change some existing situation, a curiosity about a specific phenomenon or event, or simply the need to advance your career.

- Practical goals: are focused on accomplishing something—meeting some need, changing some situation, or achieving some goal.

- Intellectual goals: re focused on understanding something, gaining some insight into what is going on and why this is happening.

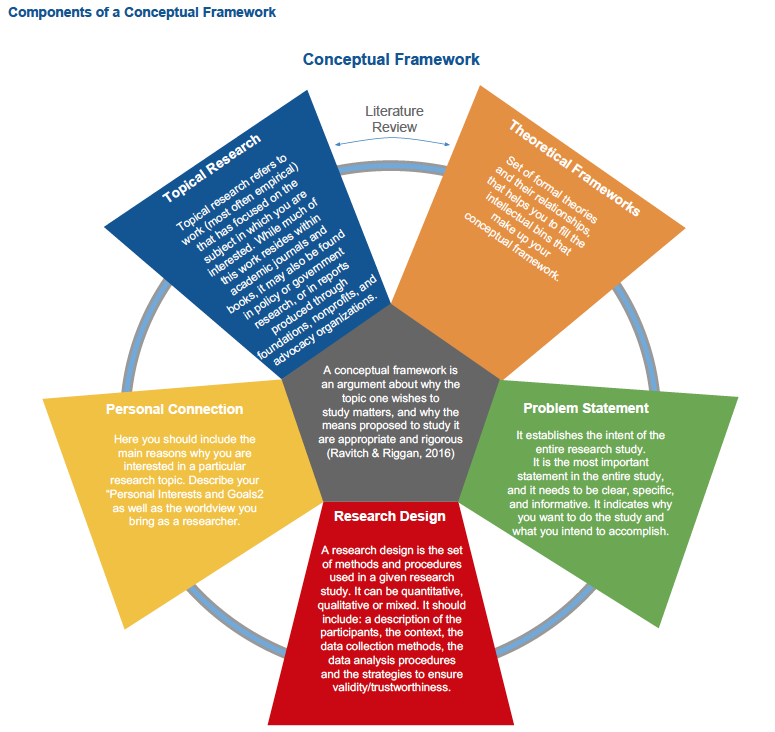

Steps and Resources to start building your conceptual framework

Steps and Resources to start building your conceptual framework

| Step 1: Identify your personal connection with your research topic |

| The following are questions that Ravitch & Riggan (2016) encourage you to explore in order to engage in a process of self-examination at the outset of your research and then iteratively throughout the research process.

What is interesting to me and why? (In terms of my research topic) What personal and professional motivations do I have for engaging in this research? How might these motivations influence how I think about and approach the topic? What are my beliefs about the people, places, and ideas involved in and related to my study? Where do these beliefs come from? What assumptions underlie these beliefs? What orientations to the topic, setting, and concepts do I have? Where do these ideas come from? What is my sense of the relationship between the macro and micro sociopolitical circumstances in which people make meaning and choices in their lives? With respect to the participants in my study specifically? What is my "agenda" for taking up this topic in this setting at this time? (Having an agenda is not necessarily a bad thing. This may be the foundation of your argument!) What influences this agenda? What biases shape this agenda? How might my guiding agenda contribute, both positively and negatively, to my research design? Implementation? Analysis? Findings? What hunches do I have about what I might find and discover? What informs these hunches? What concerns, hopes, and expectations do I have for this research? In addition to the responses to these questions, you can also take advantage of the goals defined in the second stage of the Hopscotch. There are three types of goals for doing a study (Maxwell, 2008) that could help you shape your personal connection with the selected research topic:

|

| Step 2: Identify your identity and positionality as a researcher |

| This second step is deeply related to the paradigmatic view or worldview that you will be bringing to the studyas a researcher. Please have a look at information provided within the first step of Hopscotch (Step 1: Paradigmatic View of the Researcher) in order to understand the particularities of the main worldviews you might bring to your study. |

| Step 3: Literature review |

The third and main component of your conceptual framework will be the review of literature. The following guides that have been generated by Dr. Olga Koz, Graduate Librarian at the Bagwell College of Education (Kennesaw State University) could be a great resource when working in the topical research and theoretical frameworks you will use to justify the relevance of your research topic and the need for the study you are proposing:

"Topical research refers to previous work (most often empirical) that has focused on the topic in which you are interested. While much of this work resides within academic journals and books, it may also be found in policy or government research, or in reports produced through foundations, nonprofits, and advocacy organizations." They understand a theoretical framework "as a set of formal theories and their relationships, that helps you to fill the intellectual bins that make up your conceptual framework." The following resource will be of help to identify topical research and theoretical frameworks to justify the relevance of your research topic, its pertinence and its theoretical roots. |

| Resource to search for relevant papers related to your research topic |

| Resource to generate a visual representation of your Literature review |

This form will help you build a visual representation of the topics emerging from 10 key readings that are deeply related with your research topic. The generated visual will also help you differentiate between the topical research and theoretical frameworks that will serve you to start building the conceptual framework for your research project. After filling out the form you will receive an email including a pdf document with a visual representation of the work done, as well as a link for you to modify your answers as many times as needed. In the following link you can see an example of the type of document you will get after filling out the form: goo.gl/TL9hsg The visual representation generated will help you build the literature review for your research project.

To identify the 10 articles which are most related to your research topic, or that inform your conceptual framework, you will have to read many more than 10. All articles must be primary sources and from peer-reviewed/refereed journals. To do so you can use any of the resources that we have included in the tables below (Resource to identify key topics in your field of research: Open Knowledge Map; Resource to graphically build your conceptual framework; Research guides; Science of Science (Sci2)).

You don´t have to use all of the resources provided, just the ones you believe could help you the most based on your previous knowledge. For instance, if you already know how to conduct a literature review, or how to identify scholarly articles, you might not have to use the "Research Guides." On the contrary, if you want to identify existing publications regarding your research topic, you might want to use the "Databases in Education," and "Open Knowledge Maps."

The following figure shows an example of the type of visual representation you will get after filling out the form.

|

| Resource to identify key topics in your field of research: Open Knowledge Map |

With "Open Knowledge Maps" you will be able to search for key concepts related to your research topic in order to generate a visual representation that will help you identify publications addressing that particular key concept.

|

| Resource to identify key literature in your field of research: Science of Science (Sci2) |

The Science of Science (Sci2) Tool is a modular toolset specifically designed for the study of science. It supports the temporal, geospatial, topical, and network analysis and visualization of scholarly datasets at the micro (individual), meso (local), and macro (global) levels. This tool can be used to conduct thorough literature reviews.

|

| Resource: Research Guides |

The following guides that have been generated by Dr. Olga Koz, Graduate Librarian at the Bagwell College of Education (Kennesaw State University) could be a great resource when working in the topical research and theoretical frameworks you will use to justify the relevance of your research topic and the need for the study you are proposing: The following guides that have been generated by Dr. Olga Koz, Graduate Librarian at the Bagwell College of Education (Kennesaw State University) could be a great resource when working in the topical research and theoretical frameworks you will use to justify the relevance of your research topic and the need for the study you are proposing:

|

| Resource to Define your problem statement |

| One key component of your conceptual framework will be the "Problem Statement." You can use this template to define it after having conducted your review of literature. |

| Resource to graphically build your conceptual framework |

You can use this template to create a visual representation of the main components that should be included in the conceptual framework of your research project. In order to be able to use the template, you will have to log in your Google account so the system can ask you to make a copy of it.

|

| QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TRADITIONS |

The main research traditions in qualitative research are Narrative Research, phenomenology, ethnography, grounded theory, action research, and case study. You can find a detailed description of them in the tabs above.

Narrative Inquiry is a form of qualitative research that deals with the analysis of human experience, more specifically "it studies the lives of individuals and asks one or more individuals to provide stories about their lives. This information is then retold or restoried by the researcher into a narrative chronology" (Clandinin & Connellly, 2000).

It can be understood as "the transdisciplinary study of the activities involved in the generation and analysis of stories of life experiences (for example, life stories, narrative interviews, magazines, diaries, memoirs, autobiographies, biographies) and the presentation of reports adapted to this type of research " (Schwandt, 2007, p.204).

Other authors such as Creswell (2013) also define it as "a research tradition in which the narrative is understood as a spoken or written text that accounts for an event, action or a series of events and / or actions, connect-two in chronological order ". It is convenient at this point to clarify that although the use of narrative texts, stories and vignettes is a fundamental strategy for most research traditions, in this case we refer to narrative research as a particular form of research with characteristics and own procedures . In this way and despite the fact that "narratives can be both a method of study and the phenomenon of study itself" (Pinnegar & Daynes, 2007), we will only focus on the first ones. Narrative Inquiry emerged in the decade of the nineties of the last century and has its roots in literature, history, anthropology, sociology, sociolinguistics, and education; different fields of study that have also adopted their own approaches within this tradition of naturalistic research (Chase, 2005).

This type of research has been supported by the turn towards narrative and autobiography that has taken place in the social sciences, the result of postmodernist thinking and the lack of faith in the traditional discourses of the positivist paradigm. This new paradigmatic situation, described as the era of "blurred genres" (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994), arose as a response in the 70s and 80s to a variety of paradigms, theories, methods and research strategies , that from a criticism of faith to positivism advocated more interpretative-naturalist approaches for the study of social phenomena.

In narrative inquiry stories constitute the fundamental data for the researcher, which have come to be called "field texts". Usually these are collected through interviews and conversations that are then used to generate detailed portraits of the informants, in order to document their voices in a certain social and cultural framework.

Generally, the researcher compiles the stories of his informants, between one and five, and then "re-story" them (Creswell, 2013, p.74) according to a series of themes that emerge from them. The new story / narrative generated by the researcher can be structured around a chronology of events that describe the person's past, present and future experiences, always located within a specific socio-cultural context or context.

When putting into practice a narrative study it is convenient to follow a series of steps that under our point of view are masterfully summarized by John Creswell (2013) in the following way:

1. Determine if the research problem fits the characteristics of narrative research: it is advisable to use this research tradition when we intend to capture the detailed stories or life experiences of a single person or the experiences of a small number of individuals.

2. Review of the literature: Narrative researcher place in the foreground the experiences of the participants and relegate to the background the academic literature related to the research topic. They generally find the underlying direction and structure of their research reports in the participants' history rather than through a formal review of the literature.

3. Select between one and five informants with interesting stories and life experiences around the topic of research: Narrative researchers usually spend extended periods with their informants in order to capture their stories in their own words. For this they collect information in multiple formats (field texts, field notes, letters, photographs, videos, artifacts created by informants, etc.).

4. Collect information about the context of the informants' stories: It is vitally important to situate the stories within the personal experiences of the participants in their work, family, cultural, political and historical environment.

5. Analyze the stories of the informants in depth: The narrative researcher must generate a process of detailed analysis of the stories of their informants to later be able to "chronicle" them around a set of topics that make sense within the proposed study.

6. Verify the accuracy of the narrative report generated: Although John Creswell does not include this last step among his specific recommendations for the implementation of narrative research, we have considered it appropriate to include it as a final stage since it is of vital importance for the credibility of a study of these characteristics. The triangulation of data and the processes of checking with the informants (member checking) the consistency of the information shared with the researcher, are crucial to adequately represent the voices and life experiences of the informants.

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what narrative Inquiry is:

You can generate a visual representation of your narrative study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

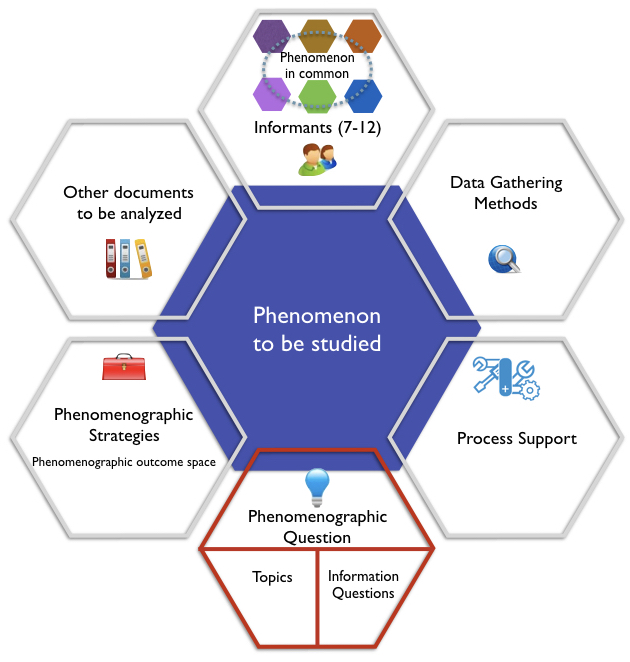

A phenomenological study describes the meaning of the experiences lived by a person or group of individuals regarding a certain concept or phenomenon. For example, a research focused on the study of how a group of young people have experienced "Bullying" in secondary education, could be phenomenological if we focus our attention in the analysis of the common aspects experienced by them. Like the rest of the research traditions within the qualitative approach, phenomenology is not ultimately interested in explanation, but in reaching a deep understanding of a phenomenon from the eyes (frame of reference) of the person who has experienced it.

When designing a phenomenological (trascendental) qualitative study, the main steps to follow according to Moustakas (1994) are:

a) In the first place, the researcher must ask himself if his object of study really constitutes a phenomenon that can be investigated from this research tradition. As we anticipated earlier, this particular form of research focuses on understanding the way in which a group of individuals have experienced a certain phenomenon. The central thing will be, therefore, what their experiences have in common, not the personal history of each one as it would happen in a narrative investigation.

b) Secondly, the researcher must describe in depth the phenomenon that will focus the study.

c) Third, the researcher must submit his preconceptions about the phenomenon under study to a suspension process or "Bracketing" called "epoche." For this, the researcher must "suspend" his or her preconceived ideas about the phenomenon, to better understand it through the voices of the informants in his study.

d) In the data collection phase, the researcher generally develops in-depth interviews with a group of 7-12 participants who have experienced the phenomenon under. Usually the researcher opens the interview by asking two only questions to the interviewee: The first one related to their experience of the phenomenon; and the second related to the contexts and previous lived situations that he considers have affected him to experience the phenomenon under study, in the way he has done it.

e) In the data analysis phase, the researcher proceeds to the identification of dimensions or units of meaning that emerge from the in-depth interviews; these units are transformed into "clusters" of meanings, expressed in the form of psychological and phenomenological concepts. Finally, these transformations lead to a general description of the experience, the "textual description" of what the participants experienced and the "structural description" of how the phenomenon under study was experienced. Subsequently, starting from the "structural description," the researcher generates a composite description, called "essential" that brings together the essence of the phenomenon or invariant structure. This is derived from the common experiences described by the participants, making clear the underlying structure of the faith-phenomenon under study.

The following clip describes in a visual manner what phenomenological studies are:

You can generate a visual representation of your phenomenological study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

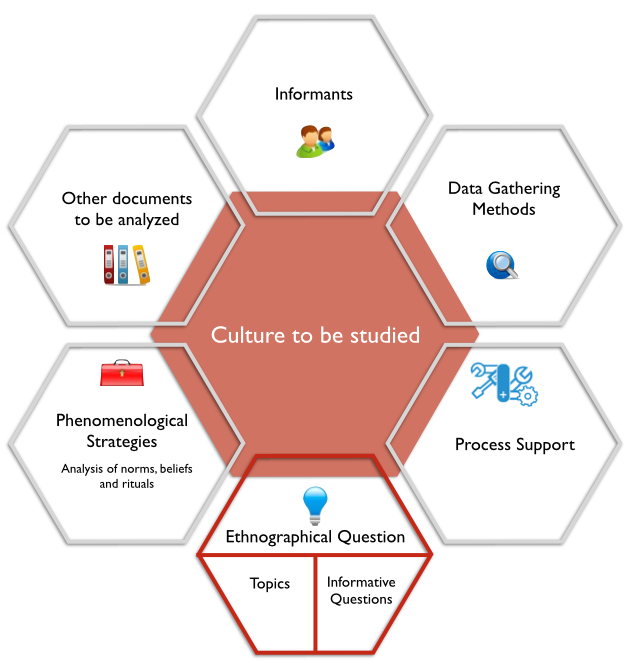

Ethnography is a research tradition widely used in the social sciences that arises from cultural anthropology and qualitative sociology. We speak of ethnographic research or simply of ethnography, to allude both to the research process by which one inquires, learns and reflects on the way of life of a certain social group, as well as the final product (ethnographic portrait) of that research.

Hammersley and Atkinson (2007) define ethnography as the study of social interactions, behaviors, and perceptions that occur within social groups, teams, organizations, and communities. Therefore, the ultimate goal of this tradition is the analysis and detailed understanding of the particularities of a given social group. Due largely to this last aspect (the study of the particularities of a social group), we see that in some qualitative research manuals, the terms ethnography and case studies have been used indistinctly. From our point of view, there is a great conceptual difference between these two research traditions.

In ethnography, the researcher uses a macroscopic approach to study the social norms, rituals and perceptions of a particular social group; while in case studies the researcher uses a microscopic approach, based on the analysis of the singularity and uniqueness of the actions developed by the participants of a system with clearly defined limits.

A particular type of ethnography is the so-called school ethnography (Erickson, 1973). Although we can not directly apply all the approaches that govern traditional ethnography to school, we can establish certain parallelisms that allow us to use this tradition for the study of educational problems. Regardless of whether we want to conduct an ethnographic study on the performance of a group of teachers or students; or even a curriculum, we must understand the school context as a small social community with specific norms, rituals, values and beliefs.

Although all ethnographic studies must evolve and adapt to the demands that emerge from the field, it is important to define the main steps we can take when developing an ethnographic study. Creswell (2013) establishes the following:

a) First we must determine if ethnography is the most appropriate research tradition to study our research topic. We can use an ethnographic design if, as we said before, we are interested in describing and understanding the culture of a certain social group, its beliefs, its language, the rituals of its members, their behaviors. In the specific case of school ethnography, we will refer, therefore, to studies in which we intend to analyze, for example, the reasons why an educational center is innovative, or even the impact that the collaboration culture of a school has that they can successfully develop a learning community.

b) In the second place we must identify a social group with a shared culture that allows us to study it in detail (i.e. an educational center, an association to help relatives of people with disabilities, a sports team, a neighborhood action group, etc.). The ethnographic study will be more feasible if the members of the social group have lived together for a prolonged period of time, so that their shared language, behavior patterns and attitudes are identifiable.

c) When planning our study following this tradition of research, we must select subjects that embrace the analysis of the culture shared by its members. Some examples of topics that could be analyzed under the umbrella of ethnography are: the study of enculturation processes, the socialization processes of children and young people, the way in which they learn, the analysis of inequality, etc.

d) Subsequently we must collect information in the places where the group develops as such. In the spaces where its members work, live and interact on a daily basis.

e) Finally, we must analyze the data collected in a holistic way, trying to identify defining features and cultural patterns that help us understand the functioning of the group under study.

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what an ethnographical study is:

You can generate a visual representation of your ethnographical study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

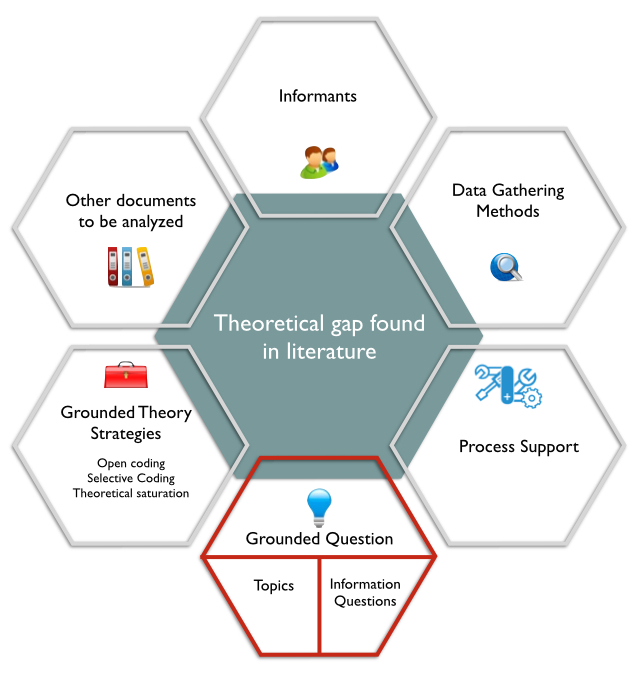

Grounded Theory is a research tradition strongly influenced by symbolic interactionism, which was raised and developed by the sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). This, unlike those presented previously, offers the possibility for the researcher to generate theory through a systematic process of data collection and analysis. This tradition of research assumes that the behaviors that occur naturally in social contexts can be better analyzed from the generation of "bottom-up" categories and concepts. Glasser and Strauss (1967) define GT "as the discovery of theories from data systematically obtained from social research." Grounded Theory was initially developed in the nursing school of the University of California in San Francisco, with the aim of generating theories that supported the studies on the awareness of the proximity of his death, had patients in terminal state .

Glasser and Strauss proposed an innovative methodology that would help them investigate a topic that had not been previously investigated. As we mentioned earlier, his new methodological proposal was rooted in symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969).

According to symbolic interactionism, the meaning of a certain behavior is formed from social interaction. Therefore, this line of thought emphasizes the importance of meaning and interpretation as essential human processes. People create shared meanings through their social interactions, which will later define their reality. GT is very effective at exploring in a holistic way, both the relationships of a particular social group and the behavior of its members, insofar as they affect the life of the individual.

Grounded theory is especially recommended for the study of situations, phenomena and contexts that have not been studied enough, and on which there is not enough literature. Its essential characteristic is that theoretical propositions are not postulated as in other research traditions at the beginning of the study, but that generalizations emerge from the data themselves and not prior to the collection of them. Therefore, theories are constructed on the basis of interaction, fundamentally based on the actions, interactions and social processes that take place between people. Charmaz (2006) proposes the following phases for the implementation of the Grounded Theory:

1. Identification of our area of substantive interest: As it happens in the research traditions previously shown, a study based on GT must also start from the identification of an area of interest and research topic. In the case of this tradition, the selection of the area of interest and the specific topic of research, as well as relying on the personal interests of the researcher, must be based on the identification of an area whose theoretical development has not been satisfactorily covered in the literature. The identification of a theoretical "gap" will provide us with the starting point for the definition of our research design. However, unlike what happens in the rest of the research traditions, at this time we should not conduct a formal review of literature, just an initial screening that allows us to identify the aforementioned lack of theoretical support of the topic that we wish to study.

2. Data collection: As established by (Charmaz, 2006, Strauss & Corbin, 1990) the fundamental techniques of data collection in GT are observations, interviews, document analysis, and in some cases, even the collection of quantitative data from, for example, the completion of questionnaires, the use of social networks or even formal techniques of discourse analysis. The decisions regarding the data collection techniques to be used will be strongly directed by the informants included in our study. Both the data collection techniques and the informants will determine the quality and completeness of the emerging theory of the process. Strauss and Corbin (1990) offer the following recommendations in this regard: a) The context, group and / or individuals to be studied should be chosen on the basis of the main research question; b) The types of data collection techniques that will be used should be chosen according to their convenience to capture the information that we seek to generate our theory; c) In the case of longitudinal studies, it is necessary to make a decision about whether to follow an individual throughout the process, or certain individuals at different points in the process.

3. Open coding and axial coding of data: As we mentioned before, when we carry out a GT study, the data collection and analysis happen simultaneously. The first step in the analysis is based on data coding. Holton (2007) identifies two fundamental types of coding; the substantive (substantive coding) and the theoretical (theoretical coding). The substantive coding aims to conceptualize the empirical substance of the studied topic, that is, to help us analyze the data in which the theory is submerged (grounded). On the other hand, the theoretical coding helps us conceptualize the way in which the substantive codes are related to each other and are integrated to form our emerging theory. Strauss & Corbin (1990) identify three fundamental types of substantive coding: open coding, axial coding and selective coding. Open coding consists of scrutinizing the data (usually texts) by separating them into units of content, or codes, in order to identify concepts, ideas and meanings contained therein. The meticulous examination of the data allows us to identify, and what is more important, to conceptualize meanings in the analyzed texts. To implement this coding strategy, we must examine, segment and compare the data in relation to their similarities and differences. For this, the researcher conscientiously reads the texts under analysis and identifies portions of them that point out ideas, concepts and / or meanings, relevant for the understanding and conceptualization of the topic subject of study. The codes generated from the researcher's interpretation are called "open," while those that come from textual phrases mentioned by our informants (in an interview, for example) are called "in vivo." At the end of an open coding process we will obtain a list, generally extensive, of codes that, when compared and reduced among them, will allow us to obtain a classification of the second degree, composed of the so-called analysis categories (San Martín, 2014). Once the process of open encoding of our data has been concluded, and having obtained a set of categories of analysis, we will proceed to the axial coding. Through axial coding, the researcher identifies possible relationships between the categories obtained in the open coding, grouping them and / or sub-dividing them into sub-categories, as appropriate.

4. Production of "memos": During the open coding and the axial coding of the data, the researcher must annotate in an organized way the decisions that he is taking, as well as the abstractions that he generates. The so-called "memos" are notes that researchers generate as they codify the data, which allows a written record of abstract thinking when creating codes and categories. Strauss and Corbin (1990, p.197) define them as "written records of analysis." The generation of memos is essential in GT because it constitutes a process of reflection by which researchers interpret the data in an analytical manner in order to discover emerging patterns that help develop the sought after substantive theory.

5. Selective coding of data: As mentioned previously, the third type of substantive coding is the so-called selective coding. It occurs as an extension of the axial coding, characterized by a higher level of abstraction. This third coding process is intended to help the researcher identify what the authors of the grounded theory call the "core category." This allows the researcher to express the phenomenon of research through the integration of the categories and sub-categories of open and axial coding. The central category that results from a selective coding process must group the categories in the axial coding phase, in order to explain the phenomenon or phenomena studied in our research.

6. Search for abstract theoretical codes: In parallel to the realization of axial and selective coding, the researcher must also begin to develop what is called "theoretical coding." Unlike the three procedures of substantive coding previously described, in the theoretical coding the researcher tries to identify a series of theoretical codes that allow him to develop an integrated and explanatory substantive theory of the phenomenon object of study. A theoretical code consists of the relational model through which all previously identified codes and substantive categories are related to the central category.

7. Review of the literature: Until now, it is not recommended to carry out an exhaustive review of the literature related to the phenomenon under study. This should be done around the category or central categories emanated from the previous phase. It is in this moment of the investigation when the existing literature in the field will allow us to generate our emergent or substantive theory.

8. Generation of the emerging theory and its integration with preexisting knowledge: GT focuses on the generation of what is called "substantive theory." This differs from formal theory, of a universal nature, in that the substantive theory deals with a type of theoretical construction of inductive order, which allows us to understand singular social realities. The substantive theory is generated from the dynamic analysis of data and therefore differs from the deductive and static nature involved in the processes of generation of formal theories. It is to this particular type of theory, to which we will refer in this eighth phase of the process of implementing a study supported by Grounded Theory.

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what Grounded Theory is:

You can generate a visual representation of your Grounded Theory study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

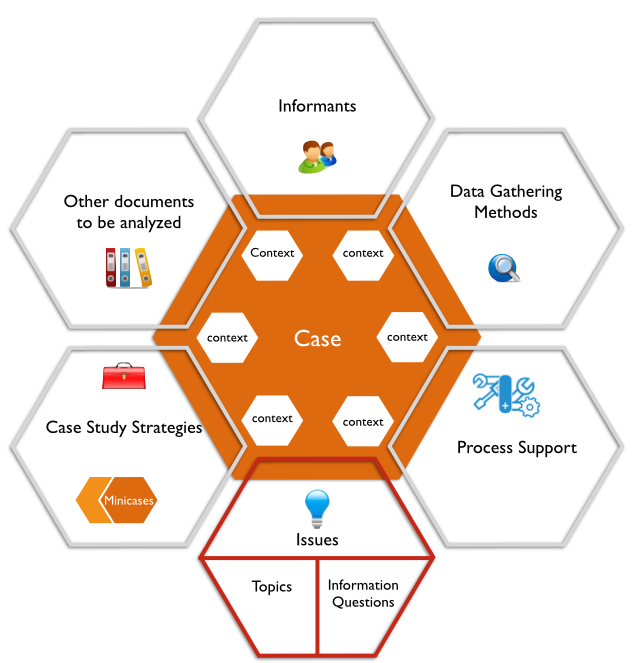

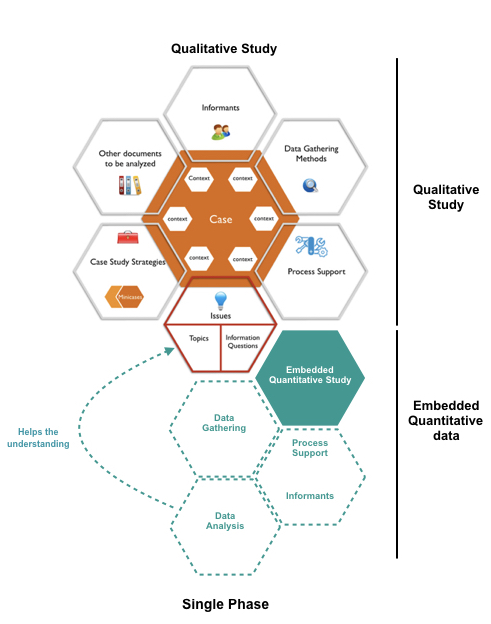

Case Study is a research tradition that allows the in-depth analysis of particular social realities, or as MacDonald and Walker (1975) indicate, for the study of well-defined systems in action. This is a tradition that has been used since we have historical records (Flyvbjerg, 2011). However, case studies as we understand them today have their origins at the end of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, in interpretative studies carried out in anthropology, psychology, history and sociology (Simons, 2009).

The main definitions of this tradition reveal that a case study, as proposes by (Rodríguez Gómez et al., 1999), implies a process of inquiry characterized by detailed, comprehensive, systematic and in-depth examination of the case under study. However there are many approaches to this tradition of research.

Yazan (2016) states that the three most relevant case study approaches in the social sciences have been proposed by Robert Yin, Sharan Merriam and Robert Stake. The three approaches differ fundamentally in the worldview or paradigmatic position from which they were conceived, as well as in the practical procedures they propose. Yin makes his proposal from a positivist position, while Merriam and Stake propose their models from constructivistic conceptions that align better with qualitative studies. Therefore, from this moment we opted for the existentialist model proposed by Stake (1995) since we consider that it has had the greater impact in the social sciences, perhaps because of the refinement of its proposal and its recommendations of practical application .

For Stake (1995), a case study should allow us to understand in depth and holistically, empirically, empathically and interpretively the person, innovation or program object of study. To do so, the researcher should focus on the observable actions of the informants that are part of the case, instead of analyzing their perceptions of attitudes and beliefs. These research design follows a progressive approach (progressive in focus) so they are flexible and they adapt to the problems and tensions identified by the informants as the study evolves. Despite the widespread belief that this type of studies do not allow the researcher to generalize their results, it does facilitate a particular type of generalization called naturalistic (Stake, 1998). The in-depth study of particular situations clearly delimited, allows that third parties in similar contexts can learn from the conclusions obtained in a specific case study.

It is important to distinguish the typology of the case object of our study in order to design it properly, and always keep in mind the ultimate objective with which we study it. Stake (1995) identifies three types of case studies depending on the purpose of the study:

a) Intrinsic case study: The intrinsic case study is conducted to learn about a unique phenomenon which the study focuses on. The researcher needs to be able to define the uniqueness of this phenomenon which distinguishes it from all others; possibly based on a collection of features or the sequence of events.

b) Instrumental case study: The instrumental case study is done to provide a general understanding of a phenomenon using a particular case. The case chosen can be a typical case although an unusual case may help illustrate matters overlooked in a typical case because they are subtler there.

c) Multiple case study: The collective case study is done to provide a general understanding using a number of instrumental case studies that either occur on the same site or come from multiple sites.

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what a Case Study is:

You can generate a visual representation of your Case Study study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

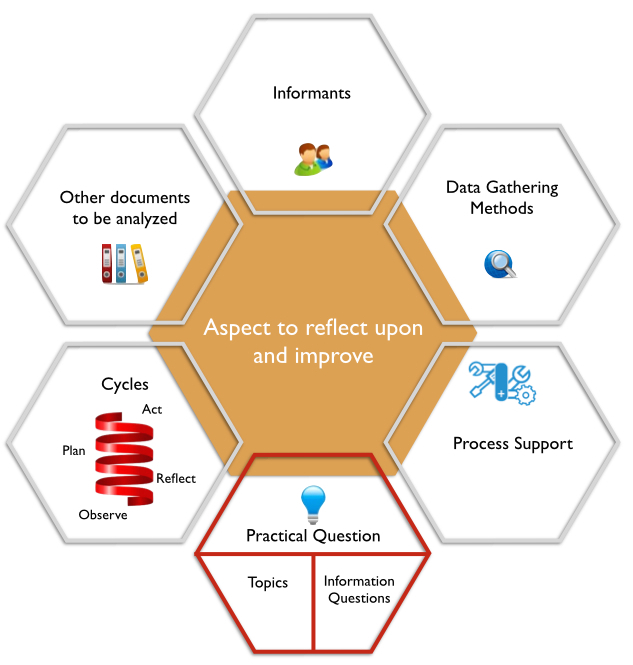

Action research (A-R) is the research tradition most oriented to the educational practice of the six presented by Hopscotch. From this tradition, the essential purpose of the research is not the accumulation of knowledge about teaching-learning, or the understanding of the educational reality, but, fundamentally, to provide information that guides a decision-making process and the innovation and change processes for the improvement of a given reality or issue. Therefore, the main goal of action research is to improve the practice instead of generating knowledge about it (Elliott, 1993).

Berg (2001) raises the existence of three fundamental types of action research: a) Technical Action Research; b) Practical Action Research, and e; c) Emancipatory Action Research. Each of them presents a different goal and it is based on a different worldview. Technical Action Research aims to "prove a particular intervention / innovation based on a specific theoretical framework" (p.186). Supported therefore in post-positivist explanatory positions. Practical Research-Action, on the other hand, "seeks to improve practice" (p.186), thus sustaining itself in an interpretive position that allows the discovery of social meanings. Finally, the emancipatory or critical Action Research has as the essential objective of social, political or personal change; its roots can be found in a transformative paradigmatic position. Currently, practical and emancipatory A-R predominate, thus framing a large percentage of the studies supported by this research tradition in the interpretative and critical paradigms (transformative Cosmovision).

However, and from our point of view, the emancipatory / critical A-R constitutes the approach that we understand should govern the studies carried out by and for teachers. We believe that a teacher should not only face a practical problem in the classroom, but should face the study of that problem from a social perspective that might help him to better understand its origins and structure, thus favoring a social change in the end.

Within the emancipatory/critical A-R, we also found participatory A-R (Kemmis and McTaggart, 2005). It is a form of Action Research that differs from conventional research in three ways. First, it focuses on research whose objective is to allow and promote action. This is achieved through a reflection cycle, through which participants collect and analyze the data, to later decide what action should be followed to improve the practice. The resulting action is then re-investigated in an iterative reflective cycle that perpetuates data collection, reflection and action. Second, participatory A-R pays close attention to power relations, advocating that power be shared deliberately between the researcher and the researched. Third, participatory A-R contrasts with less dynamic approaches and argues that those being investigated should actively participate in the process. Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) specify some of the characteristics of this particular form of A-R:

a) It constitutes a social process: participative A-R studies the relationship between the individual and the social sphere of any phenomenon under study. As we mentioned earlier, when a teacher investigates his own practice, he does it by understanding it as an educational process that has close relationships with the prevailing social model.

b) It is participatory: participatory A-R promotes that people examine their knowledge and the way in which they interpret themselves and their actionS in the surrounding social context. It is therefore participative since we can only conduct A-R about ourselves, as individuals or as a collective.

c) It is practical and collaborative: participatory A-R encourages people to examine social practices (communication, production and social organization) that relate them to other people in social interactions.

d) It is emancipatory: participatory A-R allows people to free themselves from the constraints imposed by social structures that limit their self-development and self-determination.

e) It is critical: participatory A-R helps people to free themselves from the constraints generated by social media, through which they interact.

f) It is reflexive: participatory A-R investigates the reality to change it, and changes the reality to investigate it. That is, it proposes a constant cyclical process of questioning and transforming people's practices through a cycle of critical and self-critical analysis, action and reflection.

g) It transforms theory and practice: participatory A-R aims to articulate and develop both theory and practice through a process of reflection and criticism about them. Therefore, it involves addressing daily practice from the people involved in it, to "explore the potential of different perspectives, theories and discourses that help illuminate particular practices and practical situations, as a basis for the development of critical understandings and ideas on how Things must be transformed. " (Kemmis and McTaggart, 2005, p.568).

The following clip summarizes in a visual manner what Action Research is:

You can generate a visual representation of your Action Research study using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

Phenomenography, denotes a research tradition aiming at describing the different ways a group of people understand a phenomenon (Marton, 1981), whereas phenomenology, aims to clarify the structure and meaning of a phenomenon (Giorgi, 1999).This research tradition, aims at identifying and interrogating the range of differentways in which people perceive or experience specific phenomena (typically learning, teaching or aspects thereof).

References:

Online Resources:

Phenomenographic or phenomenological analysis: does it matter?

Making sense of ‘pure’ phenomenography in information and communication technology in education

The Concepts and Methods of Phenomenographic Research

The following clip summarizes what phenomenography is:

You can generate a visual representation of your phenomenography using this tool. It will help you create a visual like the one you can find below.

| QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH DESIGNS |

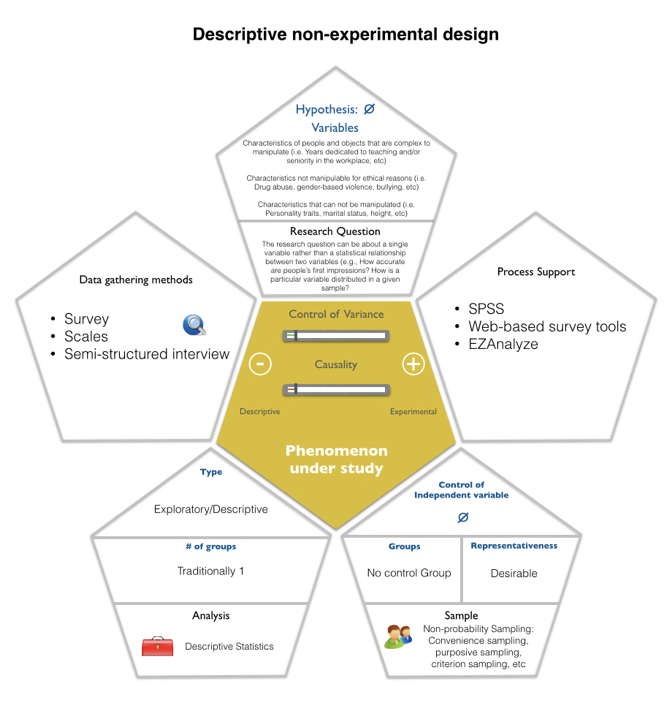

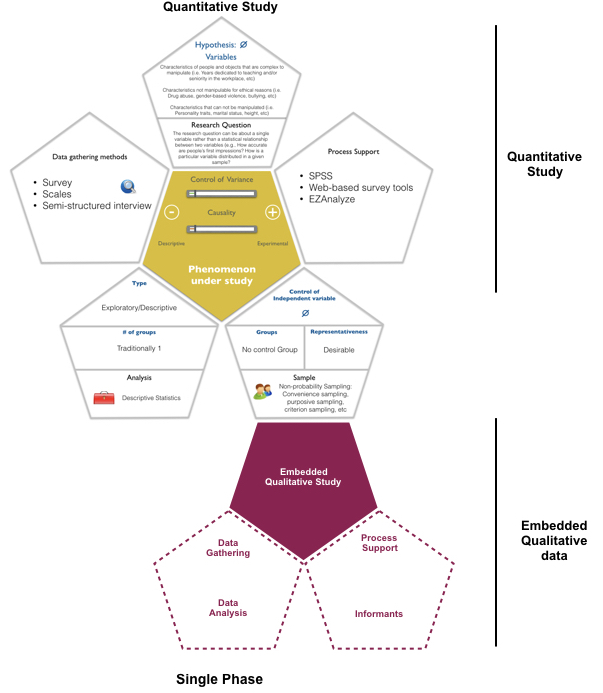

There are five main types of quantitative research designs: descriptive, correlational, pre-experimental, quasi-experimental and experimental. The differences between the four types primarily relates to the degree the researcher designs for control of the variables in the experiment. You an find a detailed description of them in the tabs above.

Descriptive designs are intended to describe an educational situation or reality and / or classify it in a certain category. They are very frequent in education and in general in the field of social sciences. Most of the descriptive studies are carried out through questionnaires or observations. Hence, the types of descriptive designs that can be carried out are survey-research and observational.

An example of descriptive design tries to answer the following question: what is the use of mobile phones by teenagers throughout the day? It is interesting to know the following variables: the daily time dedicated and the differential frequency of use of Whatsapp, social networks, and calls.

Survey-research: The main objective of a survey-research design is to describe features or characteristics of a group or population through the responses provided by the participants to a questionnaire or interview administered by the researcher. They seek to collect information referring to the entire population, and in cases where this is not possible, a sample that represents it. The main instruments in this type of design are questionnaires and structured or semi-structured interviews. The information collected through the questionnaires is usually of two types: a) sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, such as gender, profession, age, etc., and b) attitudes, opinions, perceptions, behaviors, habits, experiences, etc. Because the objective of these designs is to see the distribution of a certain variable -for example, the opinion of people over 65 years of age regarding the digitalization of the health system in Madrid- in the entire population -persons of 65 who live in Madrid-, it is vitally important that when this is not possible, a sample is selected through the probabilistic sampling procedures that allow to represent the population from which it has been extracted and thus generalize the results. In addition to the rigor in the selection of the sample, another of the decisive questions in this type of research is the validation of the instrument that will be used when it is prepared by the researcher.

Observational designs: Observation is defined by Martínez-González (2007) as the act of looking carefully at something without intervening in its natural course, with the intention of examining it, interpreting it and obtaining conclusions. The fact of being talking about observing, may introduce some confusion with the observation used in qualitative research. In this case, we are referring to an intentional, planned, structured observation, registered in an objective manner, and seeking the explanation of the observed phenomenon. That is, what is observed is quantified by different criteria such as frequency, intensity, domain, etc. One of the most complicated aspects of an intentional observation is the work that needs to be done to define what needs to be observed. For example, if we want to observe the attachment behavior of children with their teacher in early childhood education, we must explicitly and clearly specify which behaviors characterize each type of attachment in order to identify them when conducting an observation. It will also be necessary to determine if what matters is the appearance of the behavior, its frequency, or perhaps the registration of patterns of relationship between the teacher and the child. To carry out this process we have to be very sure that a certain behavior expresses what we want to measure. Hence the difficulty to observe internal aspects of the human being, which have a difficult manifestation sometimes to interpret, such as moods, thoughts or even emotions. As described in the case of survey-research studies, the measurements of an observational study can be carried out over time (longitudinal) or at a single moment (cross-sectional). The most frequently used observational designs can be found in the clinical field. The instruments for collecting observational information in a quantifiable way are observational codes, some of them already elaborated, validated and published for use in samples determined according to context and age. Control lists or estimation scales are also common.

You can use the following tool to generate a visual representation of a Descriptive non-experimental design:

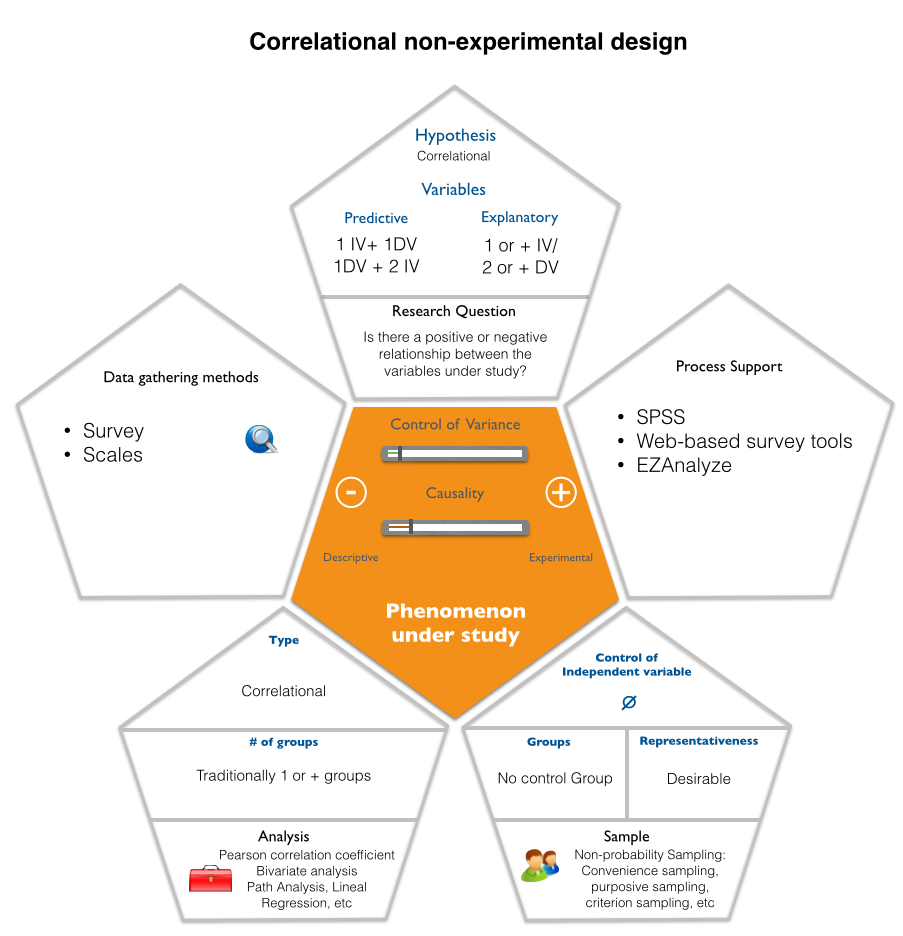

A Correlational Design explores the relationship between variables using statistical analyses. However, it does not look for cause and effect and therefore, is mostly observational in terms of data collection. A correlational study determines whether or not two variables are correlated. This means to study whether an increase or decrease in one variable corresponds to an increase or decrease in the other variable.

There are three types of correlations that are identified:

Positive correlation: Positive correlation between two variables is when an increase in one variable leads to an increase in the other and a decrease in one leads to a decrease in the other. For example, the amount of money that a person possesses might correlate positively with the number of cars he owns.

Negative correlation: Negative correlation is when an increase in one variable leads to a decrease in another and vice versa. For example, the level of education might correlate negatively with crime. This means if by some way the education level is improved in a country, it can lead to lower crime. Note that this doesn't mean that a lack of education causes crime. It could be, for example, that both lack of education and crime have a common reason: poverty.

No correlation: Two variables are uncorrelated when a change in one doesn't lead to a change in the other and vice versa. For example, among millionaires, happiness is found to be uncorrelated to money. This means an increase in money doesn't lead to happiness.

There are essentially two reasons that researchers interested in statistical relationships between variables would choose to conduct a correlational study rather than an experiment. The first is that they do not believe that the statistical relationship is a causal one. The second reason that researchers would choose to use a correlational study rather than an experiment is that the statistical relationship of interest is thought to be causal, but the researcher cannot manipulate the independent variable because it is impossible, impractical, or unethical.

The two main types of correlational designs are:

Explanatory Correlational Design: An explanatory design seeks to determine to what extent two or more variablesco-vary. Co-vary simply means the strength of the relationship of one variable to another. In general, two or more variables can have a strong, weak, or no relationship. This is determined by the product moment correlation coefficient, which is usually referred to as r. The r is measured on a scale of -1 to 1. The higher the absolute value the stronger the relationship.

Prediction Correlational Design: Prediction design has most of the same functions as explanatory design with a few minor changes. In prediction design, we normally do not use the term explanatory and response variable. Rather we have predictor and outcome variable as terms. This is because we are trying to predict and not explain. In research, there are many terms for independent and dependent variable and this is because different designs often use different terms.

You can use the following tool to generate a visual representation of your Correlational Design:

Pre-experiments are the simplest form of research design. In a pre-experiment either a single group or multiple groups are observed subsequent to some agent or treatment presumed to cause change.

Types of Pre-Experimental Design

One-shot case study design: A single group is studied at a single point in time after some treatment that is presumed to have caused change. The carefully studied single instance is compared to general expectations of what the case would have looked like had the treatment not occurred and to other events casually observed. No control or comparison group is employed.

One-group pretest-posttest design: A single case is observed at two time points, one before the treatment and one after the treatment. Changes in the outcome of interest are presumed to be the result of the intervention or treatment. No control or comparison group is employed.

Advantages of pre-experimental designs:

As exploratory approaches, pre-experiments can be a cost-effective way to discern whether a potential explanation is worthy of further investigation.

Disadvantages of pre-experimental designs:

Pre-experiments offer few advantages since it is often difficult or impossible to rule out alternative explanations. The nearly insurmountable threats to their validity are clearly the most important disadvantage of pre-experimental research designs.

You can use the following tool to generate a visual representation of your Pre-Experimental Design

Quasi-experimental designs examine cause-and-effect relationships between or among independent and dependent variables. However, one of the characteristics of true-experimental design is missing, typically the random assignment of subjects to groups. Although quasi-experimental designs are useful in testing the effectiveness of an intervention and are considered closer to natural settings, these research designs are exposed to a greater number of threats of internal and external validity, which may decrease confidence and generalization of study's findings.

Nonequivalent control group designs: The most common subset of quasi-experimental research designs are the nonequivalent control group designs. In one implementation of this design, subjects in the control group are intentionally matched by the researcher to subjects in the treatment group on characteristics which might be associated with the outcome of interest. This matching can be done at the individual level, resulting in a one-to-one match of individuals in the two groups. Another approach is aggregate matching, in which researchers select a control group with the same general composition of relevant characteristics (for example, the same proportion of females and the same age distribution) as the treatment group. These approaches are considered quasi-experimental due to the fact that assignment of subjects to groups is intentional and not random. Another common approach to this type of quasi-experimental research design is the use of existing groups. For example, a comparison could be made between students in two classrooms, with the stimulus administered in only one classroom.

Time-series data Designs: Another quasi-experimental approach involves time-series data, in which researchers observe one group of subjects repeatedly both before and after the administration of the treatment. This can be done in a controlled experimental setting, but this design also lends itself well to a more naturalistic setting in which data are commonly collected on a group of subjects and researchers are interested in the effects of some treatment or intervention which they did not experimentally apply. For example, researchers might examine the yearly test scores of students at a given school for several years both before and after the implementation of an extended school day; in this situation the yearly tests scores represent the time-series data and the change to an extended school day is the naturally occurring, quasi-experimental treatment. This approach is an improvement over the single pre-test/post-test design, which is unable to demonstrate long-term effects. The time-series data design can be further improved by including a control group which is also examined over time but which does not experience the treatment; such a design is termed a multiple time-series design.

While quasi-experimental designs are often more practical to implement than true experiments, they are more susceptible to threats to internal validity. Special care must be taken to address validity threats, and the use of additional data to rule out alternate explanations is advised.

You can use the following tool to generate a visual representation of your Quasi-experimental Design

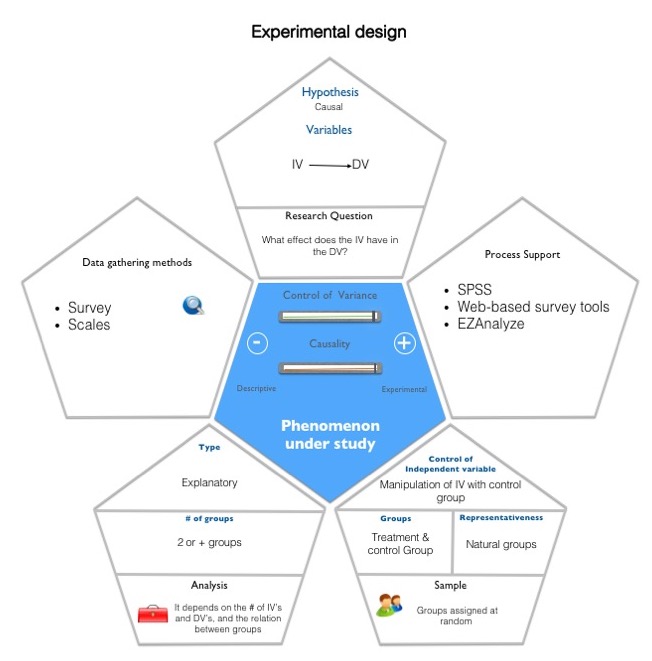

An experiment is a study in which the researcher manipulates the level of some independent variable and then measures the outcome. Experiments are powerful techniques for evaluating cause-and-effect relationships. Many researchers consider experiments the "gold standard" against which all other research designs should be judged. Experiments are conducted both in the laboratory and in real life situations.

True experiments, in which all the important factors that might affect the phenomena of interest are completely controlled, are the preferred design. Often, however, it is not possible or practical to control all the key factors, so it becomes necessary to implement a quasi-experimental research design.

In an experiment, the researcher manipulates the factor that is hypothesized to affect the outcome of interest. The factor that is being manipulated is typically referred to as the treatment or intervention. The researcher may manipulate whether research subjects receive a treatment and the level of treatment.

Example of true experiment: Suppose, for example, a group of researchers was interested in the causes of maternal employment. They might hypothesize that the provision of government-subsidized child care would promote such employment. They could then design an experiment in which some subjects would be provided the option of government-funded child care subsidies and others would not. The researchers might also manipulate the value of the child care subsidies in order to determine if higher subsidy values might result in different levels of maternal employment.

Random Assignment

-Study participants are randomly assigned to different treatment groups

-All participants have the same chance of being in a given condition

-Participants are assigned to either the group that receives the treatment, known as the "experimental group" or "treatment group," or to the group which does not receive the treatment, referred to as the "control group"

-Random assignment neutralizes factors other than the independent and dependent variables, making it possible to directly infer cause and effect

Random Sampling

-Traditionally, experimental researchers have used convenience sampling to select study participants. However, as research methods have become more rigorous, and the problems with generalizing from a convenience sample to the larger population have become more apparent, experimental researchers are increasingly turning to random sampling. In experimental policy research studies, participants are often randomly selected from program administrative databases and randomly assigned to the control or treatment groups.

Advantages of Experimental Designs

The environment in which the research takes place can often be carefully controlled. Consequently, it is easier to estimate the true effect of the variable of interest on the outcome of interest.

Disadvantages of Experimental Designs

It is often difficult to assure the external validity of the experiment, due to the frequently nonrandom selection processes and the artificial nature of the experimental context.

You an use the following tool to create your Experimental Design

| The following resources might also be of further help in order to decide the quantitative design that best fits the needs of your study: |

| MIXED METHODS RESEARCH DESIGNS |

There are three main types of mixed-methods designs: Convergent parallel, Exploratory sequential; and Explanatory sequential. You can find a description of each of them in the tabs above.

The previous three basic designs can then be used in more advanced mixed methods strategies.

For instance, transformative mixed methods is a design that uses a theoretical lens drawn from social justice or power as an overarching perspective within a design that contains both quantitative and qualitative data. The data in this form of study could be converged or it could be ordered sequentially with one building on the other.

An embedded mixed methods design involves as well either the convergent or sequential use of data, but the core idea is that either quantitative or qualitative data is embedded within a larger design (e.g., an experiment) and the data sources play a supporting role in the overall design. A multiphase mixed methods design is common in the fields of evaluation and program interventions. In this advanced design, concurrent or sequential strategies are used in tandem over time to best understand a long-term program goal.

Convergent parallel mixed methods is a form of mixed methods design in which the researcher converges or merges quantitative and qualitative data in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research problem. In this design, the investigator typically collects both forms of data at roughly the same time and then integrates the information in the interpretation of the overall results. Contradictions or incongruent findings are explained or further probed in this design.

Explanatory sequential mixed methods is one in which the researcher first conducts quantitative research, analyzes the results and then builds on the results to explain them in more detail with qualitative research. It is considered explanatory because the initial quantitative data results are explained further with the qualitative data. It is considered sequential because the initial quantitative phase is followed by the qualitative phase. This type of design is popular in fields with a strong quantitative orientation (hence the project begins with quantitative research), but it presents challenges of identifying the quantitative results to further explore and the unequal sample sizes for each phase of the study.

Exploratory sequential mixed methods is the reverse sequence from the explanatory sequential design. In the exploratory sequential approach the researcher first begins with a qualitative research phase and explores the views of participants. The data are then analyzed, and the information used to build into a second, quantitative phase. The qualitative phase may be used to build an instrument that best fits the sample under study, to identify appropriate instruments to use in the follow-up quantitative phase, or to specify variables that need to go into a follow-up quantitative study. Particular challenges to this design reside in focusing in on the appropriate qualitative findings to use and the sample selection for both phases of research.

An embedded mixed methods design involves as well either the convergent or sequential use of data, but the core idea is that either quantitative or qualitative data is embedded within a larger design (e.g., an experiment) and the data sources play a supporting role in the overall design. A multiphase mixed methods design is common in the fields of evaluation and program interventions. In this advanced design, concurrent or sequential strategies are used in tandem over time to best understand a long-term program goal.

| Once you have picked one mixed-methods research design, you can use the following links in order to generate a visual representation of the different key elements in your design: |

|

Your research questions—what you specifically want to learn or understand by doing your study—are at the heart of your research design (Maxwell, 2008). They connect to all the other components of the design Models of design that place the formulation of research questions at the beginning of the design process, and that see these questions as determining the other aspects of the design, don’t do justice to the interactive and inductive nature of qualitative research. The research questions in a qualitative study should not be formulated in detail until the goals and conceptual framework (and sometimes general aspects of the sampling and data collection) of the design are clarified, and should remain sensitive and adaptable to the implications of other parts of the design. Two functions:

- To help you focus the study (the questions’ relationship to your goals and conceptual framework) 2- To give you guidance for how to conduct it (their relationship to methods and validity) Main problems in the development of Research Questions: 1- A common problem in the development of research questions is confusion between research issues (what you want to understand by doing the study) and practical issues (what you want to accomplish ) (practical goals Vs. intellectual goals). Your research questions need to connect clearly to your practical concerns, but in general an empirical study cannot directly answer practical questions such as, “How can I improve this program?” or “What is the best way to increase students’ knowledge of science?”

- A second confusion, one that can create problems for interview studies, is that between research questions and interview questions. Your research questions identify the things that you want to understand; your interview questions generate the data that you need to understand these things.

Resources to help you develop your research Questions

Developing Research Questions in Qualitative Studies

Developing Research Questions in Quantitative Studies

Developing Research Questions in Mixed-methods Studies

| QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS |

The main data gathering methods used in qualitative research are:

- Observation

- Interview

- Focus Group

- Document Analysis

The following documents might help you better understand the implications of using the different data collection methods that are traditionally used in qualitative research:

- An overview of Quantitative and Qualitative data collection methods

- Four methods for collecting qualitative research

Please Watch the following clips to get a description of the previous methods:

Focus Groups Interviewing and Observing

Focus Groups

| QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS |

- An overview of Quantitative and Qualitative data collection methods

- Developing a questionnaire/survey

- Adopting or Adapating an existing instrument/survey

- Tips for quantitative analysis of data

- Tools to analyze quantitative data

| MIXED METHODS |

| QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS |

The following resources might be of help to better understand the way data analysis work in qualitative research studies:

Please watch the following clip to better understand the different coding procedures that ar traditionally used in qualitative research.

| QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS |

| MIXED METHODS |

| QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS |

Guba (1981) proposes four criteria that should be considered by qualitative researchers in pursuit of trustworthiness:

a) Credibility (in preference to internal validity): One of the key criteria addressed by positivist researchers is that of internal validity, in which they seek to ensure that their study measures or tests what is actually intended. According to Merriam, the qualitative investigator’s equivalent concept, i.e. credibility, deals with the question,

“How congruent are the findings with reality?”

Some strategies to assure credibility are:

- Adoption of appropriate, well recognised research methods

- Triangulation via use of different methods, different informants, different sites, and moments.

- Tactics to help ensure honesty in informants

- Debriefing sessions between researchers

- Description of background, qualifications and experience of the researcher

- Member checks of data collected and interpretations/theories formed

- Thick description of phenomenon under scrutiny

- Examination of previous research to frame findings

b) Transferability (in preference to external validity/generalizability): External validity “is concerned with the extent to which the findings of one study can be applied to other situations”. In positivist work, the concern often lies in demonstrating that the results of the work at hand can be applied to a wider population. Since the findings of a qualitative project are specific to a small number of particular environments and individuals, it is difficult to demonstrate that the findings and conclusions are applicable to othersituations and populations. Because of that we use “Naturalistic Generalization” (Stake, 2005). Naturalistic generalization is a process where readers gain insight by reflecting on the details and descriptions presented in case studies. As readers recognize similarities in case study details and find descriptions that resonate with their own experiences; they consider whether their situations are similar enough to warrant generalizations.

Naturalistic generalization invites readers to apply ideas from the natural and in-depth depictions presented in case studies to personal contexts (Melrose, 2009).

Some strategies to assure Transferability are:

-Provision of background data to establish context of study and detailed description of phenomenon in question to allow comparisons to be made

c) Dependability (in preference to reliability): In addressing the issue of reliability, the positivist employs techniques to show that, if the work

were repeated, in the same context, with the same methods and with the same participants, similar results would be obtained.

In order to address dependability in Qualitative research, the processes within the study should be reported in detail, thereby enabling a future researcher to repeat the work, if not necessarily to gain the same results. Thus, the research design may be viewed as a detailed “prototype model”.

Some strategies to assure Dependability are:

-Employment of “overlapping methods”

-In-depth methodological description to allow study to be repeated

d) Confirmability (in preference to objectivity): Objectivity in science is associated with the use of instruments that are not dependent on human skill and perception.The concept of confirmability is the qualitative investigator’s comparable concern to objectivity. Here steps must be taken to help ensure as far as possible that the work’s findings are the result of the experiences and ideas of the informants, rather than the characteristics and

preferences of the researcher.

Some strategies to assure Confirmability are:

-Triangulation to reduce effect of investigator bias

-Admission of researcher’s beliefs and assumptions

-Recognition of defects in study’s methods and their potential effects

-In-depth methodological description to allow integrity of research results to be scrutinized

-Use of diagrams to demonstrate “audit trail”

Resources:

The following article addresses these issues really well:

And here it is the reference to Guba´s work: E.G. Guba, Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries, Educational Communication and Technology Journal 29 (1981), 75–91.

| QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS |

In quantitative educational research we usually consider two general dimensions in evaluating a measurement method: reliability and validity.

Reliability is defined as the consistency of the measurements. To what level will the instrument produce the same results under the same conditions every time it is used? Reliability adds to the trustworthiness of the results because it is a testament to the methodology if the results are reproducible. The reliability is often examined by using a test and retest method where the measurement are taken twice at two different times. The reliability is critical for being able to reproduce the results, however, the validity must be confirmed first to ensure that the measurements are accurate. Consistent measurements will only be useful if they are accurate and valid.

The term validity refers to the strength of the conclusions that are drawn from the results. In other words, how accurate are the results? Do the results actually measure what was intended to be measured? There are several types of validity that are commonly examined and they are as follows:

- Conclusion validity looks at whether or not there is a relationship between the variable and the observed outcome.

- Internal validity considers whether or not that relationship may be causal in nature.

- Construct validity refers to whether or not the operational definition of a variable actually reflects the meaning of the concept. In other words, it is an attempt to generalize the treatment and outcomes to a broader concept.

- External validity is the ability to generalize the results to another setting. There are multiple factors that can threaten the validity in a study. They can be divided into single group threats, multiple group threats, and social interaction threats.